Vol. 12 No. 4, October, 2007 | ||||

This paper addresses, from a critical perspective, some premises of our understanding of the library, or, in this paper, "library theory". My starting point is the notion 'userism', introduced to discussions of library and information science (or "library, information and documentation studies" in the sense of Suominen 2007) by Suominen (2002 and 2004), and employed by Noruzi (2004) to elaborate an understanding of the World Wide Web. Suominen's original formulation is as follows:

There is something particularly convincing in the claim that

(Suominen 2002). The later formulation (see Suominen 2004) is a bit different to the previous ones in that it uses expressions like "users' (citizens') interests and 'rights' to receive information", "society's and culture's interests and 'rights' to have their members informed" and "[a]uthors' interests and 'rights' to inform (Suominen 2004, 157). The second part of the argument, for instance, has to do with the freedom of speech and has major ideological significance in the societal and ideological background of public libraries in the "bourgeois public sphere" (see e.g. Vestheim 1997).

Noruzi (2004) amplifies the criticism to a triple claim that the "Web exists" (i) for users, (ii) for researchers and writers, and (iii) for society. Further, Noruzi quite correctly situates the argument in a wider sphere of social and political discussions, as follows:The growth of 'userism' in recent Web thinking can be understood partly in relation to the prevailing neo-liberalistic view of society. When human beings are reduced to customers, consumers or users, society can be reduced to a market. A critique of 'userism' is thus topical (Suominen, 2002).

The notion 'userism' as a critical notion within LIS is connected to the notion of user-orientation which, in turn, has been a programmatic concept within the discipline since the latest decennia of the 20th century. The logic of user-orientation could be expressed briefly in the following way:

Actually, interest in research on users is already present in classical library research (e.g. Berelson 1949). However, there has also been criticism of the user-orientation within LIS. Quite an explicit instance of this is Ingwersen's (1992) way to describe the "cognitive paradigm" within information science, focusing on cognitive structures with the documents and their authors, the intermediary systems and functions, as well as the users, as opposed to the user-oriented paradigm which recognizes those structures with the user only. Similarly, Hj�rland and Albrechtsen (1995), with their "domain analytic" view, find domain-specific phenomena not only on the side of the users but with the documents and the intermediation as well. Both these instances could be seen as holistic criticism of the user-oriented tradition. The view they are criticising could be called object 'userism', a view privilegin the user as the object of research within LIS, information science, or - to a degree - even within documentation studies.

However, with regard to the ideas of the ultimate legitimatisation of the phenomena under consideration, Ingwersen's as well as Hj�rland's and Albrechtsen's views seem to remain quite userist. We could define this 'userism' as legitimatisation 'userism' because of its relationship to the ultimate legitimatisation of the practices, activities, systems etc. that take place and are produced by the library and information fields. However, the critical remarks to be made on these two forms of 'userism' are related in terms of their implications. If we now attempted to define the notion of legitimatisation 'userism', it could go something like this: Legitimatisation 'userism' is a view which, in an a priori manner, reduces all the potentially intelligible justifications of an activity, a practice or an institution, like library and librarianship, to its use and to the interests of the assumed users - not taking other possible justifications under consideration as intelligible possibilities.

Defined this way, the following remarks may be made on 'userism'. Legitimatisation 'userism' works a bit like an ideology, as a kind of implicit preliminary exclusion of some possible views outside the meaningful possibilities that even can thought about. It also has some affinity with the points of departure of methodological individualism, although it doesn't necessarily imply them.

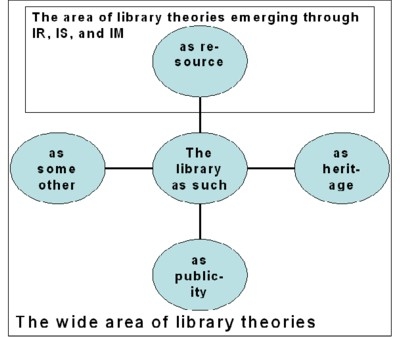

Information retrieval (IR), information seeking (IS) and information management (IM) could be seen as major subfields of LIS. Starting from these, we could form the following 'theories of the library', in quite general statements of what a library essentially is:

As regards the criticism on 'userism', the problem in conceiving the basic problems of the library and librarianship in the view of IS is that the user of the library would be the only intelligibly possible actor whose interests could legitimate the existence of a library, self-evidently and without reflection. The possible interests of society, for instance, would not have any place in this conception. Among other things, the possible educational dimension of the library could not be properly conceived of: or at least it would remain marginal and in the shadows. Of course, we could think that the promotion of information seeking would be precisely the educational interest and pursuit of society advanced through libraries. But then, this perhaps would be the only possible, legitimate educational interest and pursuit of society, if the theory of the library were reduced to the points of departure of IS. Nor the interests of those producing information (documentation, contents etc.), i.e. the interest of the authors, to have their products as part of the common and public sphere of ideas, knowledge and meanings, could have a place among the fundamental legitimatizations of the library either. IR, in turn, could in this respect be seen directly subsumed to IS. IR systems are (quite legitimately) seen as created simply to fulfil the information seeking and retrieval needs of the users; consequently, subsuming the library to their points of departure would not escape the 'userist' point of departure.

IM, however, is a different case in this respect. Here, there would be room for the interests and pursuits of the authorities maintaining, e.g. funding, the library and possibly the society as well, if the library were understood as an instance of IM. Fundamentally the idea of making knowledge (data, information) a real resource is the interest of the organization aiming at some ends, not primarily of the actual individual user, or an individual employee of an organization, for instance. The logic of IM, typically connected to organizations, is the logic of those maintaining the systems, rather than of those using them. We could think analogically of the public library system as an instance, or at least as a part of an instance of IM. The knowledge resources produced could be then of a 'softer kind', like creativity and social cohesion created by a population's reading habits, etc. - in short, as elements of what can be called a social capital.

Here, however, another problem arises. It can be summarized as the problem of conceiving of the difference between society - especially the so-named societas civilis or bourgeois society - on the one hand, and the concept of organization on the other. Within the criticism on 'userism', this can be presented as a claim that an IM based understanding of the library and librarianship does not taken into account the interests of the users and especially not the interests of the producers, e.g. authors but even publishers with primary and undeniable rights, with reference to the intellectual freedoms of the members of bourgeois society. Basically different views or 'voices', in terms of IM, would have their justification as far as they may be seen as additions to the resource. Thus, their raison d'�tre would be conditional while the logic of bourgeois society claims that the right of expression should be unconditional. This argument is, of course, dependent on our commitment to the idea of bourgeois society or societas civilis: but when considering the fundamentals of, say, the public library, we should at least consider these issues (Cf. e.g.. Vestheim's, 1997, reference to the Habermasian notion of the bourgeois public sphere in the context of the emergence of the public library).

If conceiving of the library from the perspective of IM, then, unlike IR and IS, it would be possible and even necessary to take into account the interests of the maintainers of the libraries and the authorities funding the libraries, for instance. However, even this view would be tightly connected to the notion of resource, as in the view of the library based on the notions of IR and IS. By way of a conclusion, we can state that these three subfields of LIS, if taken as a basis for a theory of the library and librarianship, are based on a view of society and culture that can be characterized as narrowly, even naively, rationalist. Furthermore, the views of the library derived from them are, in a certain way, one-dimensional, restricted to the aspects of exploiting and benefiting from knowledge, information, content etc. These views of the library could be summarized as views of the library as a resource.

In Suominen (2004), the fundamental functionality of the library and librarianship is reviewed in the light of Gadamer's (1960/1986) concept of "rehabilitation of tradition and authority". With this theme, Gadamer can be seen as returning to a pre-Enlightenment era, questioning some major claims of the modern political thinking:

...we examined the Enlightenment's discreditation of the concept of "prejudice". What appears to be a limiting prejudice from the viewpoint of the absolute self-construction of the reason in fact belongs to historical reality itself. If we want to do justice to man's finite, historical mode of being, it is necessary to fundamentally rehabilitate the concept of prejudice and acknowledge the fact that there are legitimate prejudices.

(Gadamer 1960/1986, 277.)

When Gadamer justifies the whole hermeneutical approach with a reference to "man's finite, historical mode of being", we could consider that he is speaking of the human condition that has a longer historical arch than the modernity that emerged via and since the Enlightenment. Gadamer's justification for the whole hermeneutical problem is in this way nearly existential and, consequently, nearly over-historical as far as it concerns the history of mankind.

The library is quite old as a phenomenon and even as an institution-some thousands of years old. We could even say that the library is a rather primitive phenomenon, in accordance with its relative simplicity: collecting and preserving documents. These aspects in themselves could encourage us to look for the philosophical basis from Gadamer-type considerations, focusing as they do on nearly eternal cultural fundamentals.

Tontti (2005, 58), a Finnish hermeneutical philosopher of law, draws the main lines of the hermeneutical tradition of philosophy in a most illustrative way, by characterising the Gadamerian thinking as a view of humans existing since the starting point, as an opposition to the Heideggerian emphasis of the future and of human existence as existence towards the future - or actually, with Heidegger, towards the death. With Gadamer, "man's finite, historical mode of being" especially refers to the 'back limit' of human existence, the birth, the beginning. We could formulate his view simply as follows: we all start (are born) in our turn in some moment of time, and always we start something that is already there. Here precisely would be the place of the library and librarianship too, as a representative of tradition and authority (see Suominen 2004). The library, more exactly, the content of a library, the books and other documentation, quite substantially is what is already there. In no library has there been books published tomorrow.

We can see Hoel's valid question but in a sense not so obviously the 'right answer' when he is investigating the essence of LIS in hermeneutical terms, as symptomatic of the dominant way of thinking within LIS and information science:

... information passed on by a library or information system is inevitably a record of knowledge that is from the past; there is no escape from that. That knowledge has already become historical long before it is transformed and disseminated by the system. But does this fact entail that library and information science (LIS) is by nature historical?

As far as I can see, it does not. That would be to confuse knowledge about the medium with insight into the message.

(Hoel 1992, 70.)

The hermeneutics of Hoel, like of many others within LIS (see e.g. Capurro 1992, Cornelius 1996 and Richardot 1996), seems to have a strong inclination towards understanding the human condition as being towards the future-even if not quite towards the death in the Heideggerian spirit, but more like 'towards success', perhaps-rather than as being since the starting point or beginning. The latter, being since the beginning, however, could be closer to the specific fundamental essence of the library as one particular practice related to information, documentation, knowledge, cultural contents, etc.

Gadamer's emphasis is on history and tradition; and as regards the essence of the library, I think, this is exactly what should be pondered. However, within LIS this kind of understanding is relatively rare. Shera's (1975, 49) emphasis on the "preservation and transmission of cultural heritage" as the fundamental and at the same time traditional and most important function of the library approaches this, together with the conservative element in Birdsall's (1994, 110) "politics of librarianship". Suominen (2004) draws the Gadamerian theme closer to the library and librarianship with the notion of the "authority of document", whether formal or substantial. A reliable edition of, say, Summa Theologica by Thomas Aquinas can be a rather formal authority in the sense that it can assure us that Aquinas really has written some particular sentence, chapter etc. However, for a catholic Neo-Thomist scholar, for instance, the text of St Thomas, Doctor Angelicus, could be an authority still in quite another sense, as a substantial authority, too.

Essentially, a view of the library in the light of the Gadamerian theme of the rehabilitation of tradition and authority would emphasise the essence of the library as a part of the educational dimensions and functions of the society and culture. It would connect the library and librarianship to the genuinely reproductive and, in that sense quite fundamental educational aspects. To sum up this view, we could characterise it as a view of the library as a heritage.

Yet there remains a significant issue to be made from the point of view of the Enlightenment and not least the problematic aspects of the authority in view of the modern political thinking. On a rather fundamental level, even with an explicit reference to Gadamer, the problem of tradition and criticism is expressed by Wellmer, a Frankfurt School scholar, as follows:

The course of the Enlightenment as an extension of Western Christian tradition reveals what might be called its "revolutionary core": the intention to achieve actual freedom in view of the inherited lack of freedom in practice; the spirit of criticism in view of the equally inherited legitimations of a lack of freedom. This tendency of the Enlightenment cannot be separated fro the political movements of emancipation in modern times; this connection, however, emphasizes what the Enlightenment knew and hermeneutics forgets: that the "dialogue" which (according to Gadamer) we "are", is also a relationship of coercion and, for this very reason, no dialogue al all.

(Wellmer 1969, 47.)

Within LIS, neither these aspects have been very much emphasised. A noteworthy exception must be Harris' (1986) criticism of what he calls the "American theory of librarianship" through a conceptual frame built up of the Gramscian notion of hegemony and Bourdieu's notion of cultural power. Similar to Wellmer's argument, the conceptual points of departure point exactly to the power incorporated in, and functioning through, the dialogues, communication, or discourses. Naturally, there has been some challenging of power in the literature on the libraries in terms of the somewhat programmatic views of the need to recognize different voices, as well-the Library Bill of Rights (see ALA 1948-1980) as a classical and programmatic instance. Even on the more scholarly level one could note, for instance, Tuominen's (2000) distinctly constructionist and programmatic argument that the libraries should promote "dialogue", rather than "monologue."

Yet, in the Gadamerian spirit, it is to be noted that neither critical talk nor discourse can be outside tradition and without some authority-the authority of criticism, so to speak. Actually, the Gadamerian theme discussed here would be most significant to understanding criticism, too. Without the traditions of criticism, there can only be a few different opinions, rather than true and substantial criticism.

In any case, the theme put forward by Welles does have significance, at least insofar as we are looking for the legitimatisation of the library within modern political thinking and the bourgeois society or societas civilis. This could redirect the search for the scholarly basis for the library and librarianship, from an emphasis on the notion of resource within LIS towards the notion of publicity, having a similar thematisizing position in journalism (see e.g. Boerder 2005). The library, then, could also be seen as a part and form of publicity, rather than only and self-evidently as a channel for information seeking, or as a resource and as a source of information in some other way defined.

If the library and librarianship were understood in the light of the Gadamerian theme of the rehabilitation of tradition and authority, taking also into account the aspects of criticism, and in the light of Suominen's (2002 and 2004) analysis of 'userism' and the notion of legitimatisation 'userism' introduced here, we could formulate following kind of claims about the library:

With reference especially the last point comes also the quite concrete rule that requires us to point out in a scholarly text, via a reference, our use of a previous writer's idea. This would lead to issues of the sphere of norms and ownership, which also are quite fundamental social and cultural functions, despite the legislation proper of copyright being a relatively recent phenomenon in this regard.

Here we could also open discussion on the amplification of criticism based on the notion of 'userism' to the WWW by Noruzi. Clearly the WWW is a form of publicity and dealt with as such in the research on journalism, for instance. The WWW could also be viewed as heritage, and actually is dealt with as such by the libraries, for instance by the national depository libraries. Talking about the maintainer of the WWW might be somewhat problematic but not impossible. Thus, it seems to me, Nouruzzi's amplification would have some serious plausibility.

A library theory and concept should provide us with the basis for understanding the various possible intelligible aspects of the library. It should enable us to see the different dimensions of the library and librarianship, various subsections of it, the rationalities of those subsections etc., as basically and in the first phase equally intellectually possible conceptions. It should not preliminarily exclude some of them outside the intelligible options via some too hastily assumed too concrete premises.

To attain the different dimensions of the library and librarianship, we should perhaps start from a kind of minimalist-phenomenal concept of the library, examine the phenomenon as it can be seen with the 'naked eye', and even then, in the initial phase, maintain the most fundamental features, without proceeding too quickly to the possible meaningful and intelligible functionalities of the library. In this sense, perhaps most obviously, a library is a place where there are books, or more broadly, material recordings of some contents, or documents. It is worth noting that a library as a place where there are books or documents does not exclude for instance digital libraries, if we accept some flexibility with the notion of place.

There have been libraries in the minimalist-phenomenal sense for thousands of years in various civilisations. This could open questions concerning the fundamental societal and cultural functions they may have manifested. This could naturally lead to spheres of social and cultural philosophy, even philosophical anthropology. Kauppi (1988), formerly a Finnish librarian, then teacher of librarianship and finally a professor of philosophy, uses the concept "library anthropology". This might require conceptual work outside the core areas of LIS, but some attention to these issues would be necessary if the aim is to define the library in terms of its social and cultural functions.

Figure 1, in a rough and schematic form, illustrates the situation of the various possible library theories, with regard to the minimalist-phenomenal concept of a library introduced above. Views of the library as heritage and publicity, together with the view of the library as a resource, are based on functionalities, and in that sense different from the first phenomenal-minimalist concept. However, the view of library as a resource, if taken as the self-evident, primary view of the library, would exclude the others. Suominen (2004) argues concisely how a genuine authority and a genuine resource mutually exclude each other in some respects. Clearly, similar arguments could be made with regard to views of the library as a form of publicity and as a resource, on the basis of the discussion above.

While I am suggesting here a phenomenal-minimalist way to formulate the first definition of the library, LIS and information science seem to define the library in terms of a kind of minimalist and phenomenal understanding of culture and society. It seems to be based a kind of prima facie introspection, revealing ourselves as independently-acting rational subjects and reducing the potentially intelligible understanding of our social and cultural condition only to this prima facie impression.

The library is a relatively simple and practical thing, while our social and cultural existence is a most complicated matter and hard to grasp, partly owing to the fact that what is at issue is an understanding of the fundamentals of our own existence. Consequently, while the phenomenal-minimalist first definition of the library could be plausible-even fertile-the same procedure in understanding the cultural and social condition of our being might include the risk of a highly over-simplified, even na�ve result. Further, as we have seen here, it could even lead to a relatively limited understanding of the library.

So far, I have focused on the aspects opened by the notion of legitimatisation 'userism'. The view of the library that emerges from this criticism would, however, also have implications on the objects of investigation to be emphasised. The focus should, insofar as the library and librarianship are at issue, probably shift towards disciplinary perspectives such as book history (see e.g. Finkelstein & McCleery 2005), documentation history as a part of documentation studies in Lund's (1999) sense, as the research on the forms of documentation, or bibliography as outlined by McKenzie (1986), comprehending widely the social life of books. If the library were viewed as a heritage or a form of publicity, clearly the knowledge of the materials constituting the library in this sense would be a primary area of the expertise of librarianship and a librarian. Thus the criticism of legitimatisation 'userism,' as regards our understanding of the library, could have implications concerning what I here have called object 'userism', too.

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

� the authors, 2007. Last updated: 18 August, 2007 |