Vol. 12 No. 4, October, 2007 |

||||

All professions and disciplines encounter change from within and externally, and to move forward successfully, change and evolution are necessary. Developments in the area of information technology, communication networks, the Internet and the World Wide Web, as well as the digitization of information of all kinds have set the scene for changes in many spheres, and in particular for Australian Information Management and Library and Information Science. Over the last ten years, university information management or library and information science programmes have experienced erratic or declining numbers of enrolments, closure of some library and information science schools, and changing employment opportunities for graduates. There is a need to re-think or re-conceptualize education for information in a much broader context – a context encompassing many areas of knowledge and expertise that are relevant to every sector and industry, not only the so-called information-sector.

Tensions and reforms in the Australian higher education sector and their undeniable implications for library and information science education are covered by Hallam (2006) and Harvey (2001). Two papers expand the discussion by also providing historical context relating to the problems faced (Carroll 2002; Harvey & Higgins 2003). Logan and Hsieh-Yee (2001) ably described changes in library and information science education in the American context. These contexts are global in reach, and also apply to Australia.

Trends first observed in the US are often replicated in Australia, generally about 5-10 years later. For example, Australia began experiencing the closure of schools in the mid-1990s; Australia also experienced the amalgamation or merger of small specialized schools into larger and more powerful faculties. As in the US, when competition for scarce university funds intensified, Australia struggled to maintain the number of library and information science schools it had in the 1980s with many closing in the late 1990s (ALIA 2007).

As in the US, Australia re-branded information science and library programmes by giving less prominence to library locations or settings for practice. In some instances, moves towards broadening the curricula were made to include more focus on digital and technological content and on business, commercial and non-traditional applications. These trends have been observed among schools that were merged during the late-1990s with larger faculties such as business, commerce or information systems and technology. There has been concern also over core knowledge and competencies in Australia. However, these concerns occupy less prominence in the face of shifts towards educating graduates to work in broader information environments and to consider new career paths in non-traditional agencies and organizations. Other reasons for change particularly in the Australian library and information science context include an aging academic staff profile, and the vexed and unresolved issue of whether to provide undergraduate programmes or to concentrate on post-graduate Masters’ and doctoral programmes.

Australia has yet to debate publicly the issues of convergence and collaboration with related information fields, although Harvey (2001) canvassed the idea of a Distributed Learning Network for information management or library and information science in Australia. However, universities here are so strapped for funds that discussions of the educational options possible among converging information disciplines such as represented by the “ISchool” phenomenon in the US or Europe, have not been given adequate airplay. Added to anxieties in the Australian context is a view among higher education administration that publication and research outputs of information management or library and information science faculty are less valued or are seen as less research-oriented than those of other disciplines; an especially pertinent point as Australia moves towards the new Research Quality Framework (2007) with measures that are based on a science-based model of publication performance.

In an attempt to kick-start discussions among stakeholders, the UNSW Information Management Research Group, under the John Metcalfe Foundation programme, created its “Education4Information’ Project in 2006. Interviews were undertaken during late 2006 in four Australian States with academic and teaching faculty in IM, IS (Information Systems), or library and information science programmes, university administrators, and librarians in various practice and industry environments. The project plans to expand the sample in 2008 to undertake more interviews in the disciplines of IS, KM (Knowledge Management) and IT. For this segment of the Project, staff with computer science, IT or IS training and qualifications in academia, business and industry, and in government organizations would be targeted. In this paper, responses mainly from information management, library and information science and knowledge management educators are described.

A semi-structured interview process was adopted for getting the story behind each participant’s experience. The 14 item schedule allowed for open-ended responses; each item began with a ‘stimulus’ quotation from recent literature. Interviews, lasting approximately 45 minutes each, were taped and subsequently transcribed.

A non-random stratified interview sample of ‘experts’ for whom information management or library and information science is an essential component of their occupation (N=22) was drawn from four Australian states on the eastern seaboard (see Appendix 1). General career or occupational designations are used when excerpts from interviews are quoted in order to preserve respondents’ anonymity.

The conceptual approach taken is based on grounded theory using qualitative content analysis (Glaser & Strauss 1976; Strauss & Corbin 1998). Content analysis method is used because of its power in exploring context, meaning and semantic relationships, from the transcripts of interviews (Berg 2006). The method provides for careful, detailed and systematic examination of communications to identify patterns, themes, biases, and meanings. The NVivo™ software package allowed us to categorize the content, and to identify trends, as well as similarities and differences of opinion. Categorization followed an iterative process in which there was referral back to the transcripts of interviews for verification of context. The reliability of the coding was ensured by using several independent coders, and by monitoring and comparing coding to achieve consistency and stability of concepts. Through this process, the major themes and concerns of participants emerged from the data and not from a preconceived subject classification.

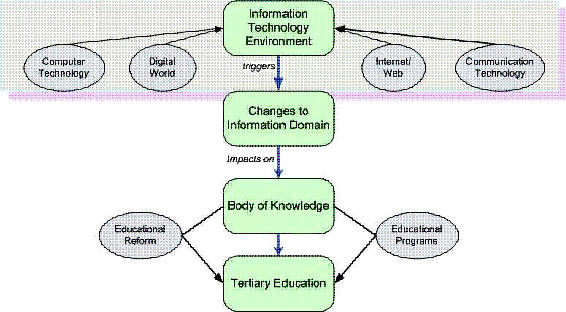

This paper presents data related to technology use and associated educational reforms. The framework presented in Figure 1 emerged from the data (using grounded theory), rather than from prior notions or theories about educational reform or agendas. The framework is based on the frequency of comment made by respondents. It shows that triggers for change arise from new uses of technology and communication networks. It also shows that facilitators for reform include society’s expectations about education for careers and jobs. Workplace requirements and expectations as triggers and facilitators of change, however, are the subject of another paper, and are not discussed here.

This paper reports on what respondents expressed as the important triggers, facilitators and barriers in the following inter-connected areas. These are listed below. The data are derived from responses to 9 questions (64%) from 16 participants (76%) (See Appendices 1 and 2).

Our respondents were asked to identify the major drivers of change in their areas of work in libraries or information services, as educators, and as administrators in libraries or educational institutions. Whatever their career status, interviewees identified similar drivers or triggers of change, and emphasized positive aspects of change, such as greater access to information resources, speed of access, and new ways of connecting to people.

Technological change pertinent to the world of information service and delivery was a focus. Respondents mentioned changes brought about by ICTs within the profession and in business and that computers and other information and communication technologies have infiltrated into the everyday life of many people.

There was universal acknowledgement that the Internet, the Web, and information and communication technologies (ICTs) have acted as change agents in many fields and professions, and particularly for the information professions. Respondents identified the nature and extent of impacts they experienced from these areas, and provided views of ways to respond to such change. The themes and topics raised are illustrated by verbatim quotes to indicate varying levels of meaning and nuance, and differences in their experience.

Interviewees frequently talked about the impact of the Internet and the networking of information as having changed the way people do their work. Some describe how these triggers also changed their own work behaviour and practice. Some older respondents are critical of student reliance on the Internet rather than using the library, but as one early-career librarian points out:

What is different now relates to the kind of information people want – now they prefer online and interactive services – the current generation is pro interactive information.

The situation is bluntly stated by a senior administrator in an academic library:

The Internet is used and that’s that … If we don’t come to grips with the use of the Internet in libraries and elsewhere, we’re lost to the users.

However, one educator accepts the reality of users preferring to search for information on the Web:

Google is not the end of libraries. On the contrary, Google is the friend of libraries because it has made people more conscious of accessing information and also more conscious of the rubbish they find – so the role of the trained intermediary is becoming more important.

Respondents also acknowledge that the Internet changed their modes of working dramatically. One young academic in a teaching department says:

Access to the Internet has changed the teaching environment and the way one has to teach now. It changes the way you have to approach teaching. Many of the undergraduates feel they ‘know it all’ and it is difficult to get them to understand [that] there is something worthwhile for them to learn about how to search and strategize searching better. This is challenging.

Libraries were very early adopters of computers with hardware and software solutions to a range of crucial activities, such as building online catalogues and sharing cataloguing through networked services. Online database use, particularly for bibliographic purposes and abstracting services, has a long history. However, despite long usage of computers in library settings, a number of interviewees mention the difficulties that mature-age career-changers still encounter in learning IT and adapting to the ubiquitous use of computers in the workplace. These career-changers are being taught alongside younger students many of whom arrive with well developed computer skills. This means that library and information science and information management programmes are forced teach IT at introductory levels that leave students with good IT backgrounds dissatisfied.

A senior educator deplores the fact that even in 2006 '�we still have to teach a great deal of IT because skills of students in this area are lacking.” Looking further ahead, this educator suggests that: '� because IT changes often and is so dynamic, perhaps we will always have to teach a certain amount of IT”. Younger interviewees propose that it should be assumed that students “…come with the basic suite of online and ICT skills. One strongly puts the view that: “ICT is …not part of the [library and information science] course at all.”

These findings accord with the “significant confusion over what every librarian should understand about IT” noted by Xu & Chen (2001: 319).

A number of interviewees speak of changes to their thinking, ways of working, and even career paths, occasioned by new technologies.

The Internet and the rise of communication networks, both these factors, changed the direction of my career significantly. …This has occupied the last 15 years of my life.

Over the course of her career, another relates that: '� IT changed how we did everything – from organization workflows that were realigned by the computer. Instead of being paper-based, we got to do things differently and more quickly”.

A senior library administrator acknowledges that:

Computers changed the nature of my work completely – so much of communicating is now done via the computer – communication with staff, stakeholders, suppliers … everything. … work is addressed differently in computers.

Younger interviewees suggest that the profession needs better understanding of new technological developments:

� and what they can do within the profession � how does it all work, for example, XML, digital library technology, electronic records management, content management � [the profession] needs to go deeper into these things.

The online environment with universal use of computers and other electronic devices has wrought many changes in service levels and access to information resources. Respondents see the traditional focus of libraries shifting away from outright ownership of resources (collection development) to provision of resources made accessible via electronic searching tools and shared resources via online subscriptions or leasing arrangements. That delivery methods have changed is hardly challenged, with frequent references to the use of mobile devices such as, cell phones or personal digital assistants, the Web, and channels other than just looking for a book or a journal article in a library. One mid-career librarian says expectations of users in relation to libraries are different than they were in the past, and she questions cogently: 'What does this mean for libraries when there are so many ways of using information?' In part response to her own rhetorical question, she suggests that libraries might best focus on service and delivery by thinking laterally and being flexible and responsive. Advocates of looking at ICTs as vehicles for the delivery of information to clients are not only the younger librarians. One senior manager states:

It is important to understand that there are different channels for delivering information that can be shared – the mobile phone, for example, may replace the PC. Information can be delivered or brought to you on your mobile phone – being aware that there is more than just the Web – there’s the IPod etc.

Many interviewees, in recognizing the power of electronic information, express the view that students need to be capable in ICT to deal with digital content. One senior manager in the information resources sector avers that:

The digital world is a major shift, including the framework of what is now possible, and how to interact in the Web world. This shift is reflected in the generational gap between the paper generation and the digital one.

She highlights some of the resultant issues:

The issue of digital libraries is clearly a challenge – libraries are becoming places for access to digital documents, but there are huge problems to deal with here such as, rights of access to the materials, preservation, use (such as who gets to use the files or documents) issues about authorization and custody rather than possession; the crux is not the ‘object’, but how ‘objects’ are managed.

The increased growth and access to digital information is highlighted by a senior academic:

� part of the access is the availability to the increasing networked information, not just the type of information, but the places to go to get that information - obviously underpinned by the Internet.

Respondents have very clear notions of what the core knowledge claims of the information management or library and information science profession are. Most agree on those areas of knowledge which remain our unique domain and stress the need to retain and even strengthen these areas. Many respondents feel quite strongly that not only is information management or library and information science core knowledge distinct from that of other fields but that it is becoming increasingly valuable for other information fields, particularly the information systems field, and for new ‘digital world’ issues. When asked about what distinguishes information management or library and information science professionals, this response from a library administrator seems to sum it up:

It is … around information evaluation, organization, management and access – and the theoretical framework around all that – in this we run rings around other professionals in our grounding and knowledge about theory and the basics, such as indexing, representation, and so on.

Another academic who has been in the education field for many years states his view that:

�the unique body of knowledge is around how people interact with information; it draws on how information is organized, how people get access to information to do the things they need to do. This is a newer focus on information behaviour. The principles still apply around organization of information.

Many see the core set of knowledge as reasonably coherent across the classic information fields of librarianship, archives, recordkeeping, or museum curatorship. Among the core skills and knowledge respondents point out cataloguing, classification in its many forms (now often labeled as ontology or taxonomy) and aspects of the curatorial roles of selection and preservation of all information records. As one educator emphasizes:

information management or library and information science content is so important because the need to manage information is ubiquitous and important – everywhere, not just in libraries.

At the same time as asserting the value of these skills, this educator also believes that we need '� a wholesale re-direction of thinking about the ways in which we represent documents, manuscripts and records, including issues relating to classification, cataloguing, descriptions, and metadata.”

Other content added to the traditional subjects includes understanding of the social implications of information, good retrieval skills, problem solving ability, and customer service. A recently graduated librarian believes that learning about the Web should be a core part of our profession and thinks that [librarians] should not only know the tool well but be able offer something better than other professions.

More than half of all respondents emphasize the importance of teaching basic concepts relating to the nature of information. As one mid-career teaching academic describes it:

The most important components of the core knowledge set is an understanding of information itself, its properties, its characteristics, its contexts, and our relationship to information and our capacity to do all that we need to do to document, describe and share information.

This view is echoed by educators who think it vital to inculcate in students

� an understanding of the way information works, in terms of being a communication process at all kinds of levels, organizational, individual, etc. � recognition of information as a substance, a product in its own right shaped by social forces and society.

Engaged in both information science and systems teaching, this educator believes that the reference literature of information management or library and information science is strong. In discussing the scope and relevance of courses for today’s needs, he says:

�it�s a case of 'What is old is new again' � some of the classic things taught as integral parts of library and information science are more important and relevant than ever. For example, document management and all the components of that right through from description of information items, to the subjective knowledge of the documentalist describing the information, and the value-adding they [professional documentalists] bring to that process. Another area is the classic skills of reference service. Some of these things have slipped to the wayside in Australia as we moved into an information systems context. These things are relevant and � there is room for them in courses as part of broad business programmes.

Communicating with clients is suggested as a core skill for information management or library and information science professionals. As one respondent expresses it: '� interaction with clients is critical � this is the difference between the 'I' world and the 'IT' world.'

A number of respondents recommend the introduction of a course on information behaviour as a general subject for all information professions or specialties. One respondent puts it succinctly: 'The main game is to get through to students that the information itself is what matters.'

Having an understanding about how different people approach information, and learning how to work through people’s needs, are fundamental skills, which many respondents think essential if information professionals are to meet clients’ demands. One library manager encapsulates this idea:

� [professionals] need to know how to access all kinds of databases, know where the information is, look at all channels, contexts.

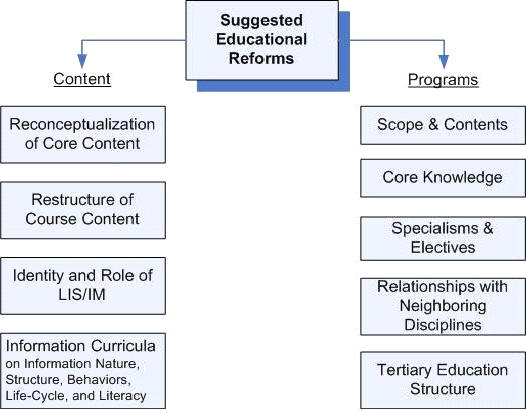

Different views and emphases emerge from the data on how to manage change within the educational curriculum (see in Figure 2). Barriers to reform seen by interviewees arise partly from the structure of the university faculty system, economically sustainable enrolments, and length of programmes. Another arises from the labels of librarianship and library science or studies which no longer seem to fit student expectations or many key employment opportunities for graduates. One could say that the labelling issue is somewhat of a hot topic. One senior manager has this to say:

The real challenge in the profession is how to differentiate ourselves to be unique in the way you manage, not always doing things the way we used to do … Innovation is critical in an organisation. It is not necessarily an efficiency gain, but a value seen in differentiation.

Another interviewee thinks that:

� the lines are very much blurred nowadays � information organizations [like libraries or museums] need to be able to respond in a much broader way about markets and where they position themselves.

An early-career level librarian emphasizes a need to look at structural change, particularly the identity and role of the library, and of professionals working in libraries. He regrets that 'a lot of people are still grounded by what or how it was done in the past' and who seem unwilling to change their roles or that of the library. He believes the profession needs: '� to develop new ways of present ourselves and the library differently'. This point about presenting the profession differently is echoed by a senior consultant in the field:

We need to reconceptualize what information is – this is a contested area and it needs to be re-thought because information is conceptualized differently among different professionals/industry/business/IT – so there is a need for a mutual understanding about what information is. Issues here include: currency, duplication, space.

In the course of the interview, respondents were asked to suggest reforms or ways of changing the curriculum to improve the programmes currently offered in Australia. The overall impression or sense is that reform and revision of educational programmes are essential in order to accommodate the inevitable changes brought by ICTs and digitalization. Many expressed the view that attention to changes in the field and the marketplace needs to be ongoing.

Respondents are critical of course structures and content when asked to specify changes or alternatives to programmes. This interviewee comments on insufficient work-related preparation:

Would have been better to have a practical component and an industry component in the course. The programme did not prepare me for what happened when I took my first job.

One respondent complains about the depth of intellectual content:

The current offerings in library and information science or information management in Australia attempt to cover everything – but not at a deep enough level.

Others believe that depth and content are limited by the duration of courses:

...a one-to-one-and-a-half-year programme can only give an introduction – too superficial really. Not in any way, shape, or form can it properly deliver the content.

In reflecting on possible reforms, some think that information management or library and information science could be given:

� a great deal more prominence at government level, even be mandated as part of curriculum. Not sure how it is to be done.

In reflecting on the scope of current courses and their relevance for today’s needs, respondents nominate types of reforms to education that might usefully be pursued. This line of questioning produced a range of views which are highlighted below.

Arising from the pervasive use of the Internet and WWW resources, several interviewees voice concern with teaching a form of information literacy that is focussed on how best to use the host of electronic resources now available. One respondent with long years of experience in libraries suggests information literacy is not only important for the general population, but that:

� the development of information literacy is vital for success in operating in economic contexts.

Again we hear the concern for students to acquire:

� a deep understanding of what the Web means in terms of information, in terms of search engines and how they work, of how to optimize them and about issues around the deep Web area, that is, what�s there and isn�t there.

Another senior person in education says that, if she were in charge of universities:

� everyone would take a one-day workshop or some other concentrated course on using the Interenet and the whole Web with a view to instilling some ideas about quality of pages/sites. To disabuse them that search engines show all of the 1000s of Web pages to them. Also to show them that many sites have questionable authority � so [we] need to teach students to use their critical faculties to identify quality resources on Web.

Ideas expressed by the younger interviewees stress that the current generation of users prefer online and interactive information: 'they don�t want to read long passages of stuff, in their everyday lives; they go more for online materials'. In line with this view is the suggestion from a senior educator that ‘digital content’ should be taught as a course 'through the life cycle of information creation, retrieval, storing, controlling, disposing, and so on'. Emphasizing this point, she believes a new digital libraries course should be:

� a capstone subject that is basic for all. This area is exciting, fundamental and requires all the former traditional Information Management skills, such as classification or taxonomy, and extends the student with digital information sources, ideas about audience needs, design of Web sites and so on.

Bawden et al’s study (2004) on education and training in Slovenia and the UK indicated that existing courses were being adapted or re-designed rather than creating new courses labelled digital library.

The many issues around digitized information concern our interviewees. All agree that the digital world is a major shift and most are concerned about issues of copyright, intellectual property, concepts of authenticity, integrity, plagiarism, ethical behaviour, and protection of records. So great are the concerns relating to the digitization of information that one researcher and manager believes that:

� whole slews of things need to be re-thought; we need to go back to the conceptual building blocks to consider the ways and the why we do things.

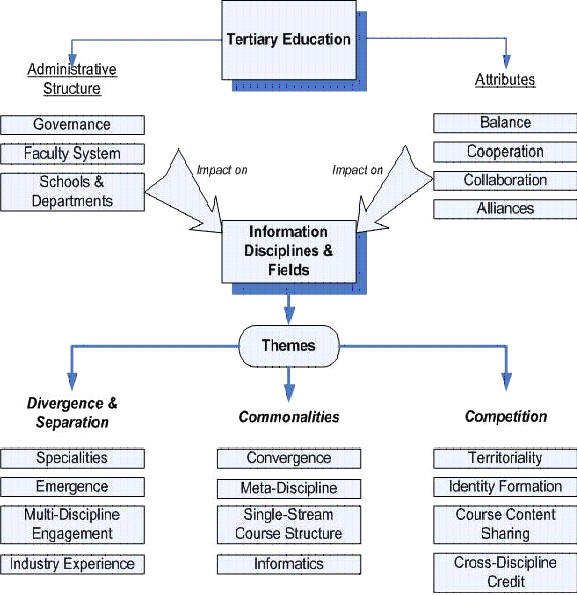

The interview schedule raised the issue of the multiplicity of related information fields and courses preparing graduates for information professions. Responses to these issues provide the evidence for developing another NVivo model (see Figure 3) which shows administrative structures and attributes necessary for change as well as the main themes respondents identified as ripe for discussion ― divergence and separation of disciplines and fields, commonalities among them, and the vexed issue of competition among the fields themselves and universities within the Australian higher education sector. Respondents also commented on their views about convergence and collaboration among the spectrum of information disciplines and professions. Other studies have concluded that collaborative partnerships in teaching are useful (see Buchanan et al. 2002 re information literacy courses). The possibility of designing a single stream as a beginning course from which graduates could continue into specialist courses in a range of fields was canvassed. All these issues were given serious consideration. Despite not having time to give fully-considered responses, and although some expressed reservations, most comments were not completely dismissive of notions of collaboration, cooperation or convergence.

One respondent suggests that:

�one would need to deconstruct what is in the core of the different information disciplines to get any idea of a single course � I would leave Computer Sciences out because it is about bits and boxes � that�s not about information management, whereas information management is on about the stuff in the box and how it behaves.

However, one respondent explodes vehemently when asked to consider convergence among information-related programmes.

I have no patience with divergence – there is a commonality among information fields that is vital and important. They are all essentially the same field with differences in manifestation; they are within the progressional range of information work.

He is of course talking about similarities and convergence, even emergence. Another respondent expresses it differently:

It seems to me to be more like emergence. We are almost a meta-discipline really; we can fit any academic and social context. I’d like to see less convergence and more emergence – more sharing with other disciplines, but it is not necessary to blend with other fields administratively.

However, the reality in Australian universities is that a major barrier to bringing the information fields closer is the faculty administrative system, which divides information-related courses. Other impediments are academics clinging to course identities and professionals to specific professional spheres. One interviewee thinks the lack of convergence is not related to the subject domain:

I’d say that mainly the cause [of non-convergence] would be due to the incompatibility of the people running the courses – because I know that there are informatics faculties in other universities, and that they work well. Yes, it’s possible to combine them [information courses] together; it’s not only possible, it’s happening, and it works in other universities.

In terms of running a single stream, course or programme for all information students, a senior academic administrator positively identifies medicine as a model, with its educational programme feeding into various medical colleges and specialties, such as, pediatrics, obstetrics, or surgery. He points out that each of these specialisms belongs in the field of medicine, yet they all commence by learning a common core of knowledge.

The survey results show a lively debate about how to accommodate specialization within current programmes, that is, on specific areas of academic or occupational interest. A recurring barrier is the inability to provide for specializations within the course structure because money is tight and so many programmes in Australia are too small (in terms of staff numbers and student enrolments) to mount specialist courses, or even to offer much in the way of electives. In this context, we note efforts to introduce evidence-based librarianship in the information management curriculum at Queensland University of Technology (Partridge & Hallam 2006).

The schedule probed to ascertain whether recognition of specific content from neighboring fields could be accepted as legitimate course credits in information management or library and information science programmes. A key barrier here is the uncertainty of getting approval from academic boards. Some spoke about encouraging students to explore their interests, while recognizing that students need guidance so that what they study is useful to them. A practicing librarian rails at strictures against students taking subjects outside the confines of information management or library and information science programmes, saying that it is:

� critical to let students undertake courses for credit outside their programme, if they are approved � it is part of the work to remain flexible and lateral thinking, bringing other kinds of thinking into librarianship.

Pie-in-the sky according to another.

Perhaps one could train undergraduates to learn information (structures and behaviour) and related philosophy, how to think, and then have them come back at postgraduate level to learn the management side of things, move to next level … that would be lovely, but it just won’t happen that way.

Less defeatist, but recognizing the reality of university governance at the moment, an experienced educator offers this comment:

I see potentially where areas are not actually competing but are increasingly addressing things we consider as in the domain of information management. All of them (information fields) are close for different reasons – and sometimes we use them as reference disciplines – and at other times, some disciplines use us as a reference discipline, perhaps not as much as they could. I see a greater need for more interdisciplinary engagement and I don’t necessarily think that we will see good examples of that while universities create this internal competition around domains.

This study exploring the current situation in education for information in Australia is one of the few to explore impacts of information technology and digitized information on academia and the information management or library and information science professions. Analysis to date shows four broad themes emerging as responses to educational reform. The major themes identified are impacts brought about by digitization of information, new communication technologies and electronic/online services, all of which demand reforms to teaching, education curricula and programmes, and training of graduates for professional careers and employment. Many sub-themes are identified under these dimensions.

The interviews have provided a rich source of data for analysis on a number of critical educational issues in Australia. The basic conceptual framework which emerges from the data highlights the important triggers, facilitators, and barriers to educational change. The findings show support for the relevance of traditional subjects of information management or library and information science and expansion of core knowledge into behavioural aspects of information use, for the need for specializations or electives, for a stronger focus on digital libraries and issues in digitization, such as IP, copyright, integrity and authentication of information.

Our analysis to date reveals that respondents have many ideas about the necessity for change; however, they did not clearly enunciate pathways to achieve desired and useful reforms. Indeed, the data reveals respondents express great variation and even uncertainty about the type and nature of the reforms needed. Some reforms suggested appear to be tinkering at the edges. All respondents expressed a desire for better communication and cooperation among all the stakeholders in the information disciplines. This is an area which is compromised by the competitive nature of current faculty and administrative structures within Australia’s university sector. Analysis indicates that information management or library and information science (e.g. library studies, information science, knowledge management, archives, & records management) continue to be rather isolated from the broader information domain as a whole leading us to conclude that attention needs to be paid to the resolution of the relationship between cognate areas relating to information, particularly given recent programme closures in Australia. Subsequent analysis will explore respondents’ views about the lack of electives within disciplinary programmes for information management or library and information science and the need for more practicum within programmes. The data also show current programmes are unable to provide students with specializations across current faculty structures.

The rigorous interview methodology and the in-depth data generated are strengths of this study. The purposive sample was able to elicit views about education for information from respondents with diverse backgrounds and experience. The schedule enabled participants to respond freely to the issues raised without restriction. Furthermore, respondents were encouraged to reflect on their own experiences, thus enhancing the validity of their responses. These factors ensured that no issue coded in the content analysis was given more prominence than another.

Despite the small sample size, which prevents generalization of the results, the study provides plenty of grist for a full discussion or debate of the issues among information professionals and educators. The difficulties encountered in these interviews, such as different professionals not talking the same language, need to be addressed in discussions among educators about curricula and programmes.

The findings indicate that in Australia there is an expressed need for information management or library and information science curricula reform and revision. Interviewees agreed on the necessity of a rational adjustment of educational programmes and open discussion among all participants within the broad information domain. All concurred that many issues have not been fully acknowledged or addressed. Analysis of the data is ongoing.

Future research to gather more data from respondents in neighboring disciplines is required in order to generalize results across the broad domain of information professions and to take account of the fast changing environment. Our research did not focus on conceptual frameworks for restructuring, although some respondents made indirect references to this issue. However, any reform remains to be resolved by committed stakeholders within the education system. In the next phase of the project, we intend to canvass views of educators about how they see these urgent concerns of revision and reform of information curricula being addressed.

This research is funded by the John Metcalfe Memorial Fund. Both authors acknowledge the support of the School of Information Systems, Technology and Management (SISTM) at the University of New South Wales. We also thank the members of SISTM’s Information Management Research Group for their encouragement and sound advice on aspects related to this project.

Q1 I’d like to open the interview by asking you to reflect on three factors of change that you think are important and which have impacted on your professional career, teaching, practice or working life. What are they, and how has each affected the way you now do things?

Q2: Reflecting on your own training and education and your preparedness for the various roles and positions you have had in your career, would you talk a little about the type of education you received and comment on its applicability and adequacy for today’s students?

Prompts: How do you view current library and information science education programmes?

Are there any changes or alternatives you would like to see in place of the current array of courses or programmes for education for information?

Q3 Tapping into your experience as an educator/manager who has been concerned with information service and delivery:

What are your views about the scope of current courses, programmes or subjects in relation to their relevance for today’s needs?

Q4 Given that information is a primary driver in the economic order of the 21st century:

What do you think is important in educating graduates for work in the new information economy?

Prompts: What are your thoughts about any educational reforms that might enable new career paths to be developed?

Could you expand on the sorts of reforms that might be pursued?

Q6 Professions have a unique “body of knowledge’ that must be acquired by those wanting to work in the profession. In your view, is this the case for information education?

Prompts: Could you briefly outline what you think are the most important components of learning needed for the information professional?

Q7 A number of disciplines or fields seem to be relevant to LIS education [example prompts: information systems, business management, knowledge management, record keeping, archives management, organizational behaviour]. Do you believe it is possible to outline a single course or programme of education for information?

Prompts: If not, why is it not possible? Could you expand on your views?

To what extent do you believe there is convergence among some of the information-related fields? Which ones?

To what extent should students in library and information science programmes be permitted to gain credit from courses/subjects in related disciplines as part of a library or information science degree program? For example, in information systems or business management?

Q9 Given the ubiquitous nature of computer and information technology in every arena of work, how important is having staff with information technology expertise as well as library and information science training?

Prompts: To what extent should information technology be taught as part of an information education programme? Could you expand on specific aspects of IT content here?

How important would you say is acquiring knowledge and skill in information systems and management?

How important is training in the area of communications technology?

How important is it to have training in technical aspects of information retrieval, automatic indexing and metadata applications?

What topics or how much, would be relevant or useful for information/LIS students to learn?

Q10 The Internet has made significant changes to the way information is provided. Is there a need for specific courses on using the Internet for information delivery in LIS educational programmes?

Prompts: In your view, is it important for information/LIS students to learn Web page design, information editing and compilation, or Web publishing skills?

Q14 Steven Schwartz, Vice-Chancellor of Macquarie University has said that graduates are ill served by a narrow focus on the utilitarian, and business and employers by the notion that universities exist mainly to confer economic benefits. Universities are not in the business solely of turning graduates ready-made for business or specific jobs; rather they are about educating students for a lifetime of learning and self-fulfilment.

Would you care to comment on this viewpoint in light of education for information management?

| Respondents |

n=21 |

|---|---|

| Age: range (in years); n | (55-64) 4 |

| (45-54) 11 | |

| (35-44) 3 | |

| (20-34) 3 | |

| Gender: n (%) | Female 14 (67%) |

| Male 7 (33%) | |

| Education degree: type (%) | Undergraduate: 21 (100%) |

| Graduate Diploma: 16 (76%) | |

| Master: 16 (76%) | |

| PhD: 6 (29%) | |

| Current position: n (%) | Educator: 7 (33%) |

| Consulting/Government: 3 (14%) | |

| Administrator/Manager: 12 (57%) | |

| Librarian: 4 (19%) | |

| Postgraduate student: 4 (19%) |

|

| Other/Information Officer: 1 (5%) | |

| Positions held previously: n (%) | Librarian: 14 (67%) |

| Educator: 11 (52%) | |

| Administrator/Manager: 11 (52%) | |

| Information Officer/Broker: 8 (38%) | |

| Consultant: 4 (19%) | |

| Archives/Records Officer: 2 (10%) | |

| Actor: 1 (5%) | |

| Chemical Analyst: 1 (5%) | |

| Book Retailer: 1 (5%) | |

| Published: n (%) | 17 (81%) |

| State in Australia: n (%) | NSW: 14 (67%) |

| VIC: 3 (14%) | |

| QLD: 3 (14%) | |

| ACT: 1 (5%) | |

| Study fields: n (%) | LIS: 10 (48%) |

| IM: 7 (33%) | |

| Education: 5 (24%) |

|

| Science (Social or Information): 5 (24%) | |

| Management: 4 (19%) | |

| History (English/Economic): 4 (19%) | |

| Engineering: 3 (14%) | |

| Politics: 3 (14%) | |

| Information Technology: 3 (14%) | |

| Literature 3 (14%) | |

| Arts: 2 (10%) | |

| Archives Administration: 2 (10%) | |

| Workplace Learning/Training: 2 (10%) | |

| Knowledge Management: 1 (5%) | |

| Psychology: 1 (5%) |

|

| Social Work: 1 (5%) | |

| Media Studies: 1 (5%) | |

| Geography and Urban Design: 1 (5%) |

| Find other papers on this subject | ||||

| © the authors, 2007. Last updated: 18 August, 2007 |