vol. 13 no. 4, December, 2008

vol. 13 no. 4, December, 2008 | ||||

Modern society is an information consuming society and as such the question of information quality is of central importance. Many users consider the Web to be a virtual library and, therefore, when an information need arises they use the Web by default (Scholz-Crane 1998; Grimes and Boening 2001). These users fail to appreciate that the inherent structure of the Web has created a new environment (Burbules 2001); that is, they do not completely internalize the difference between the publication process of printed articles and those published on the Internet. In the conventional publishing process the information not only goes through quality assessment, but it is also subject to a publication policy whereas, over the Internet, the publishing process allows almost anyone to quickly and easily publish his or her opinions. Therefore, the information retrieved does not always originate from recognized or qualified sources and possesses varying information qualities (Rieh and Danielson 2007; Metzger 2007) compelling the user to perform an independent assessment of information each time s/he searches for information on the Internet.

Quality is an elusive concept; its definition is situational and has a dual character. It is of a transcendent quality (essence) synonymous with excellence, "an essence that is neither mind nor matter, but a third entity independent of the two "�. and "[e]ven though quality cannot be defined, you know what it is."(Pirsig, 1974: 185, 213), while, at the same time quality is a precise and appraised quality that may be looked upon as a product (Garvin 1988: 40-46).

In the context of this paper the quality of information is solely dependent on whether the information is true, or in other words, whether quality equals veracity. As truth can be subjective (Jacoby 2002), here information can be accepted as true only when it conforms to an accepted standard or a pattern (Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary 2007), defined by the scientific community or by the searcher's community at large. As the appraisal of facts and determining what is true are based on personal prior knowledge, a state that is seldom present (Kahneman and Tversky 1982); therefore to assess the quality of the information, one has to rely on a surrogate mechanism, namely that of credibility. Credibility is "the quality or power of inspiring belief" (Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary 2007) and therefore conveys the impression that it is more a perception (Fogg et al. 2001; Freeman and Spyridakis 2004; Liu 2004) than an actual appraisal of facts. By contrast, in the context of the current study, credibility is not a perception nor it is a criterion for relevance judgment (Barry 1994; Bateman 1999), it is a direct measure of actual quality (Garvin 1988 : 40-46), re-created each time the question of truth arises. Hence, assigning credibility to information is not the end; rather, it is the means of accepting the veracity of information.

Patrick Wilson's (1983) epistemic authority is another theoretical concept that is closely linked to credibility, which was discussed by both Rieh (2002) and Savolainen (2007) in the context of Web searching. Cognitive authority is a quantitative concept that consists of two components, competence and trustworthiness, and is viewed as a relationship between two entities, where there has to be an acknowledgement of the authority of one entity over the other. Acceptance of the information conveyed by the authoritative party implies that cognitive authority can be found in various sources and not only in individuals. It isimportant, however, to note that one can be an expert without being regarded as an authority or be regarded as authority in one area, but not is another area (Wilson 1983: 13-15).

The concept of credibility was discussed in two extensive literature reviews (Metzger et al. 2003; Rieh and Danielson 2007). Based on surveyed populations, several studies tried to answer the questions how people evaluate Websites and their content and, if they do, what evaluation criteria are employed, how and to what extent these criteria are used (Flanagin and Metzger 2000; Liu 2004; Liu and Huang 2005; Fogg et al. 2001; Barnes et al. 2003).It seems that, when assessing credibility, attributes that pertain to the site are used more readily (Fogg et al. 2003) than attributes relating to content, implying that sites whose looks are more appealing are perceived as holding more credible content (Robins and Holmes 2008). However, there exist other studies (Rieh 2002; Stanford et al. 2002; Eysenbach and Köhler 2002), which consider attributes like author and source as key elements for evaluating the quality information, thus disassociating themselves from appearance and converging to the conventional pattern of assessing information.

People regard the Web as an important source of information and turn to it by default (Grimes and Boening 2001). Although users acknowledge the need to evaluate the quality of the information retrieved (The UCLA Internet Report - Year Three, 2003: 39), they do not always do so (Scholz-Crane 1998; Graham and Metaxes 2003), nor do they corroborate the retrieved information with other sources (Flanagin and Metzger 2000; Fallis 2004); therefore, studying methods or mechanisms whereby information quality assessment can be performed is of utmost importance.

Several methods are used by librarians and other information professionals that can be seen as substitutes for a quality control system:

Previous studies were inconclusive on the question whether users voluntarily assess the quality of information accessible on the Web. We hypothesize that as an integral part of Web information behaviour there exist what we may call information quality assessment which represents a true quality control measure that utilizes specific tools and procedures to assist the assessment the quality of information. In contrast, however, to any quality control programme, which is performed by a specially designated individual, in the case of information retrieval, quality control is performed by the user him/herself as a reflex reaction to the diverse and inconsistent quality of information.

The purpose of this study is to investigate information quality assessment of information retrieved on the Web by directly observing users' information seeking behaviour and by asking the following questions:

To answer our research questions we used several instruments; direct observation, interviews, open and closed ended questionnaires and the think aloud technique. Actions taken during tasks were monitored by using the surveillance software Spybuddy

The study population was recruited between November 2005 and February 2006 by advertising on university bulletin boards using the purposeful sampling method as described by Patton (1990: 182). When a person was recruited, s/he signed an informed consent, participated in a full research session and was then offered coupons for the university bookstore. The recruited study population was composed of seventy-seven individuals recruited from the general student (undergraduates and graduates) population at Bar-Ilan University. The majority were females (72.7% out of 77 participants), native Hebrew speakers (89.6%), who prefer to search the Web in Hebrew (79.2%) and are very frequent Web users (as 86.1% of them indicated that they use the Internet every day).

Each session started with briefly explaining that we are conducting a study about Web search behaviour, without disclosing that we are actually looking for behaviour related to information quality assessment. Then the think aloud technique (Rieh 2002) was demonstrated, an informed consent form was signed and a background questionnaire was completed by the participants. Thereafter, the session started with each participant completing two search and one evaluation tasks.

Here we only discuss the results of one of the search tasks denoted as scenario task, as this task simulates best the natural Web information behaviour (searching for information on a general topic). One of the additional tasks, the domain task, intended to disclose how domain knowledge influenced information quality assessment. The evaluation task was devised to observe isolated information quality assessment behaviour.

The topic for the scenario task was selected from the site about as suggested by Toms and Taves (2004) and the topic was social phobia. The scenario read as follows:

You have a close friend who is shy, has problems with adjusting to new situations (like new employment, dating the opposite sex) and expresses anxiety and fear when s/he has to leave the safety of home. You, as his/her best friend encourage him/her to seek professional help. The diagnosis provided was that your friend suffers from Social Phobia or Social Anxiety. Overwhelmed by this information you try to find more information on the subject using the Web.

After completing each search task participants were interviewed for three to five minutes. They were asked for their comments, the reasons for choosing or not choosing specific sites and how they usually selected information from the Web. The responses were recorded and later transcribed(Patton 1990: 348-351). Then after performing all three tasks, the participants were asked to complete a final questionnaire. It included open and closed questions relating to their views about the quality of information on the Web and the methods employed by them to ascertain it.

Based on ten randomly chosen transcripts and using content analysis (Strauss and Corbin 1990), a hierarchical tree of categories (later to be referred as components) with their relevant attributes was constructed. Using a Microsoft Excel table, each participant was identified by an ordinal number, with the results of each task for each participant (scenario, domain, and evaluation) recorded in a separate row, while attributes and sub-attributes were placed under a different column. Each time a participant noted an attribute or a sub-attribute the value one (1) was marked in the appropriate cell ( Miles and Huberman, 1994: 43-45, 253). After accepting the emerging tree of categories, transcripts of the remaining sixty-seven participants were similarly analyzed and the categorization tree was expanded and altered as the data unfolded ( Strauss and Corbin 1990: 61-76 ).

On a randomly selected 10% of the study population, categorization was corroborated by two other coders ( Merrick 1999). Only after verifying that there was an agreement between the external coders and the categorization performed by us, was the overall categorization accepted.

The scoring method expresses numerically the use of the information quality assessment components and its attributes, where an attribute is a feature of an item mentioned by participants. Each component consisted of a different number of attributes, and in order to be able to compare them the components were normalized, i.e., divided by the number of attributes of each component. There were two types of scores:

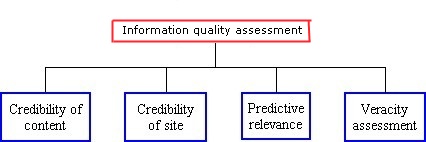

The attributes mentioned and used by the participants, defined four different evaluative components (Figure 1): credibility of site, credibility of content, predictive relevance and veracity assessment. In the following subsections we describe the attributes of each of these components. These four components comprise the core category information quality assessment.

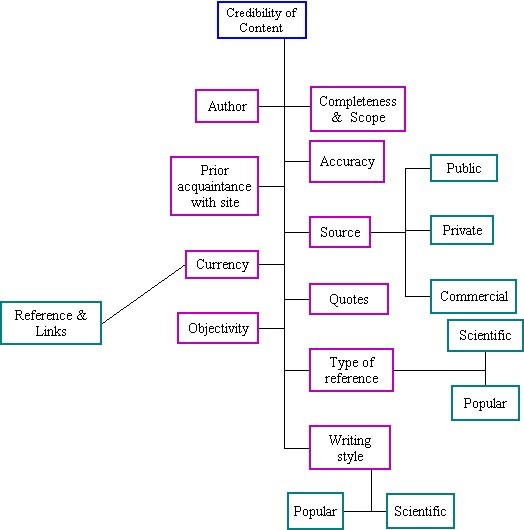

There is consensus that, for assessing credibility (referred to here as credibility of content (Figure 2)), some attributes are considered as core elements and, therefore, one expects that every credibility assessment will take them into account ( Rieh and Danielson 2007). These are: scope, accuracy, objectivity, currency and authority. However, in reality not all attributes are used ( Fogg et al. 2003) and users usually mention only one or two of them ( Scholz-Crane 1998). In our study, users mentioned and used extensively only the authority attributes.

Previous studies found that attributes that relate to authority are the main attributes people use when evaluating information quality ( Rieh 2002; Freeman and Spyridakis 2004; Eysenbach and Köhler 2002; Liu and Huang 2005) and, therefore, it is not surprising that in the scenario task more than 60% of the study population mentioned the attributes source and author where the first (mentioned by 62% of the participants) is expressed by three sub-attributes: public, private and commercial as nicely verbalized by three participants 'I see that it is Geocities�' 'It is exactly what I looked for, a non profit organization.' 'Although I see it's a .com site, it can be useful'.

The attribute author (mentioned by 70% of the participants) refers to the author's credentials, qualifications (Metzger 2007), as was stated by two participants: '�the person who wrote it is a doctor� I don't know if this doctor really exists, yet the information is helpful'. 'I am interested knowing who the author is... whether he's an expert or someone who decided to publish his thoughts'. However, the fact that participants noticed the author's name or credentials does not mean that they actually verified it.

Similarly to the findings of Flanagin and Metzger (2000), under the normative Web search behaviour (scenario task) we find that the attributes; accuracy, currency, objectivity were mentioned by very few participants. The low usage of the attribute accuracy (In the context of this study, accuracy, translated from the Hebrew, exists only in the sense of exactness and not that of truth) is explained by the participants themselves when stating that '�I really can't say whether the information is accurate or complete as I didn't study 'academically' social phobia �if I were a psychologist then I would know'.

The attributes accuracy and currency as well as the sub-attribute links and references - refers to whether the links or the references themselves are current: 'the site presents how to deal with social phobia but the links that the site refers to are not from recent years.' were also not used by many participants, as reflected in Metzger's (2007: 2083) conclusion that 'people do not seem to take the currency of the information they find online into account when making credibility judgments'.

Other frequently used attributes were: prior acquaintance with site (25%), writing style (26%), type of reference (35%) and scope and completeness (27%). The use of the attribute prior acquaintance with site is interesting as it indicates that a site has been already assessed for quality, found to be of good quality, implying that those sites have an advantage compared to other (unknown sites) as there is less need to go though the information quality assessment process and as one of the participants stated: 'I am familiar with InfoMed it is a good source'.

When evaluating an article or a book, one turns to examine whether the author included current references and what types of references were used. This behaviour was found by Eysenbach and Köhler (2002) and by the current research as well. The participants used the attribute writing style and its sub attributes scientific or popular as a sign of quality (similar to Eysenbach and Köhler 2002) as one of our participants stated: 'It's a serious article; the language is more scientific'.

The literature ( Metzger 2007; Rieh and Danielson 2007) presents scope as one of the five core attributes and, indeed, Scholz-Crane's (1998) findings indicated this criterion should be considered as one of the most important criteria for evaluation information quality. However, in contrast to the extensive use of the authority attributes (author and source) by the majority of participants (over 60% of them) only 27% of our participants used the attribute scope and completeness preventing us from ascribing this attribute as one of the core attributes.

Previous studies suggested that the appearance of a site and its design are pivotal when evaluating the overall credibility of that site. However, when prior knowledge about the subject exists (Eastin 2001; Rieh 2002; Stanford et al. 2002) people emphasize the evaluation of the quality of the information (Liu and Huang 2005; Stanford et al. 2002; Jenkins et al. 2003) more than the appearance of the site.

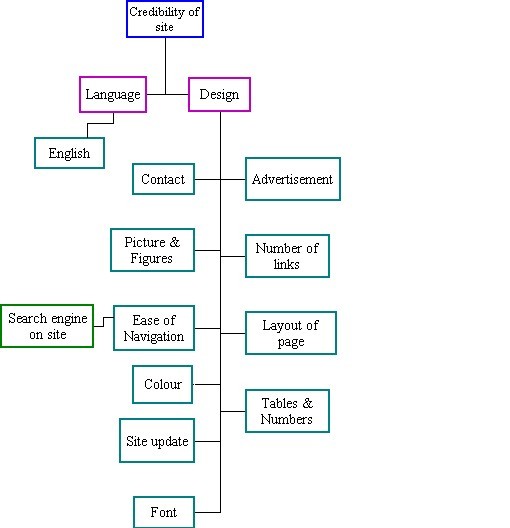

Attributes that were mentioned and used are presented in Figure 3, where the main attributes (coloured magenta) of credibility of site are design and language. The attribute design is expressed by several sub attributes:

The attribute language depicted herein denotes a preconceived idea that sites written in English are more academic that those written in Hebrew as expressed by one of the participants 'Because the terminology is in English I will choose this site� it looks more scientific'.

Barnes et al. ( 2003) found that when participants evaluate Websites they relied more on the design and aesthetics criterion, than on the authority attributes while the present study indicates that only 19% and 23% of the participants used the attributes tables and numbers and layout respectively. Freeman and Spyridakis ( 2004) concluded that the presence or absence of links did not significantly affect credibility ratings; which may explain the fact that only 31% of our participants used the attribute number of links.

When looking for information, on one hand, one looks for the most relevant information to a specific query and topic (Bateman 1999; Wang and Soergel 1998) while on the other, one needs to reduce the amount of information retrieved. Although predictive relevance is conceptually related to relevance, it is also akin to Hogarth's ( 1987) predictive judgment as the users judge the relevance of the search results before accessing the site.

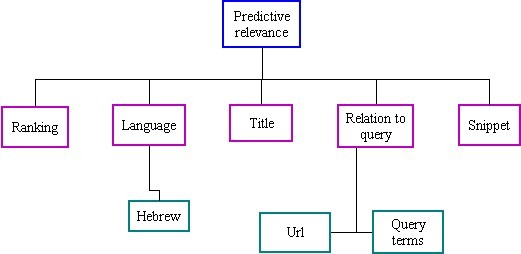

The use of this component (Figure 4) suggests that the users predict the relevance of the search results based on the ranking of the results by the search engines, the snippets and other characteristics of the search results like the title of the retrieved document and the occurrence of the query terms in the title, in the snippet or in the url of the search result, as explained by two participants: 'the first results are most relevant so I usually look at them', 'I look at the title and the abstract (snippet) to see if it matches what I asked.' , 'I usually look at the URL, and then I can see that it has no relevancy to social anxiety [because the query terms do not appear in the url].'

People prefer to use their mother tongue when searching the Web ( Eysenbach and Köhler 2002) as well as when assigning relevance (Hansen and Karlgren 2005). Therefore, language, an attribute of predictive relevance, serves here as a filter to information as participants not only searched exclusively in Hebrew but if additional information was linked to English sites they automatically exited the site, as expressed by one of the participants 'I wouldn't enter this site, because of the language - English'. As can be seen this attribute is different from the attribute language of the component in credibility of site, where there the presence of the attribute language (such as English) increases the credibility and the reputation in the eyes of the users, whereas in the case of the component predictive relevance the attribute language serves as a filter to reduce the amount of relevant sites. Although language has an impact on (predictive) relevance as 18% of our participants used this attribute, the attributes snippet and ranking were the most frequently used attributes of this component, mentioned by 32% and 30% of the participants respectively.

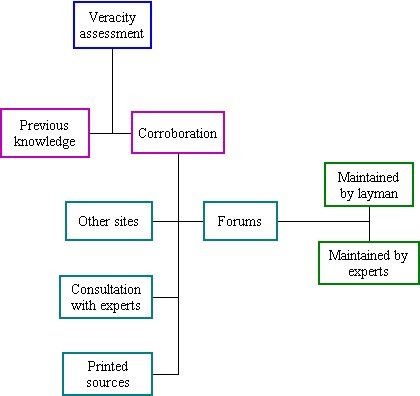

It was Descartes who said 'if one wishes to know the truth, then one should not believe an assertion until one finds evidence to justify of doing so' ( Gilbert et al. 1993: 221 ), thus positioning truth as pivotal for accepting information. Hence, to ascertain the veracity of information one should 1) compare and corroborate the information retrieved on the Web with other sources (Meola 2004); 2) ascertain authority; and 3) compare the information retrieved on the Web with personal knowledge (Haas and Waerden 2003). Therefore, the attributes defining the component veracity assessment (see Figure 5) were previous knowledge (as expressed by a participant 'from my knowledge, I know that socio is society�') and corroboration. The latter seems to be the default, whereby one will try to expand the pre-existing knowledge by corroborating the newly acquired information with other sources. Several sub-attributes of corroboration were identified by us:

Attribute scores are the reflection of the number of times an attribute is mentioned by the participants; therefore, the extent and rate of the attribute use, and by extension of component use, defines behaviour. Hence, attributes mentioned by participants during observation are actually used and, therefore, each component and attribute of the information quality assessment process is not a perception it is rather a tool to be utilized for direct appraisal of the quality of information. We envisage the use of information quality assessment as if the user has at his disposal an array of attributes integrated into four different components and utilizes them as the need arises. However, it seems that there is a small preference in usage of certain components as is shown in Table 1 where participants used more readily the components (and therefore its attributes) credibility of content and predictive relevance, more often than the components veracity assessment and credibility of site, suggesting that for our participants, like for participants in other studies, ( Stanford et al. 2002; Rieh 2002) the information has to be both credible and relevant, before being assessed for its veracity or presentation. Note that the normalized group score measures the extent of the use of a specific component on average, i.e., the participants in this experiment used on average 16.6% of the attributes available for the component credibility of content..

| Component | Normalized group component score (N=77) |

|---|---|

| Credibility of content | 16.6% |

| Predictive relevance | 13.7% |

| Veracity assessment | 9.2% |

| Credibility of site | 7.2% |

Based on our data, we suggest that information quality assessment is an integral part of the overall Web search behaviour, as all participants performed to some extent a kind of information quality assessment. Information quality assessment is intimately linked to the basic need of people to ascertain the truth; it is composed of components and attributes that represent an actual behaviour. Hence, attributes mentioned by participants during sessions are actually used and, therefore, each component and attribute of the information quality assessment process is not a perception but rather a tool to be used for direct appraisal of the quality of information.

Similar to other reports ( Metzger 2007), we also found that, when evaluating quality, participants tend to use only few of the conventional evaluation criteria. Previous studies showed that users link credibility to authority ( Rieh 2002; Fogg et al. 2003; Eysenbach and Köhler 2002; Liu 2004). Similarly, the main finding of this study is that the participants, regardless of their previous knowledge on the subject or experience in Web use, use the attributes author and source as primary attributes to assess quality. It seems as if in order to evaluate quality the use of these attributes not only lessens the need to use other attributes, but it constitutes a natural behaviour were one tries to assess truth by asking questions like: Who said it? Who wrote it? What is the source of this information? We have further shown, like Eysenbach and Köhler ( 2002), that, for non native English speakers, language may be an obstacle. We have noticed that language has become an important attribute of predictive relevance together with the attributes ranking and snippets.

The study shows that Web users always, although not always knowingly, perform some rudimentary information quality assessment, where newly introduced Web features such as ranking and snippets are integrated with the classical attributes of authority to generate a new mechanism to ascertain quality.

Results presented in this paper are part of the Ph.D dissertation of Noa Fink-Shamit, carried out under the supervision of Judit Bar-Ilan at the Department of Information Science, Bar-Ilan University.

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

© the authors, 2008. Last updated: 15 December, 2008 |