vol. 13 no. 4, December, 2008

vol. 13 no. 4, December, 2008 | ||||

This is a study of the information behaviour of members in a specific kind of organization, namely voluntary youth organizations working for peace, democracy or sustainable development. That information and knowledge are essential for organizations in a so-called 'information society', more than traditional resources such as capital or raw material, has been claimed by many, practitioners and theorists alike (see for instance Eschenbach and Geyer 2004: 9-13). Most people who have ever been members of any kind of organization can confirm that communication problems are among the more severe as well as the more usual problems in organizations. The right information, at the right time, in the right place, in the right fashion, can make the difference between good and bad strategic decisions, knit the participants in an organization together and help them pursue the same goals, facilitate tasks at all levels, and provide the participants with a common 'memory' of how problems were solved earlier in the organization. For small voluntary organizations lacking many traditional resources, information is an even more important resource: "information is the life blood on which they depend" (Deacon and Golding 1991: 69). Some voluntary organizations pursue very important and 'big' goals. The authors were interested to examine how the tension between these high ideas and poor resources manifests in information behaviour of the members of voluntary organisations and how it in turn affects the outcomes of their activity.

The basic goal of research, as some may notice, is formulated in terms of activity theory, which is presented further on. This theoretical framework and the goal have influenced the selection of a particular case and design of the study.

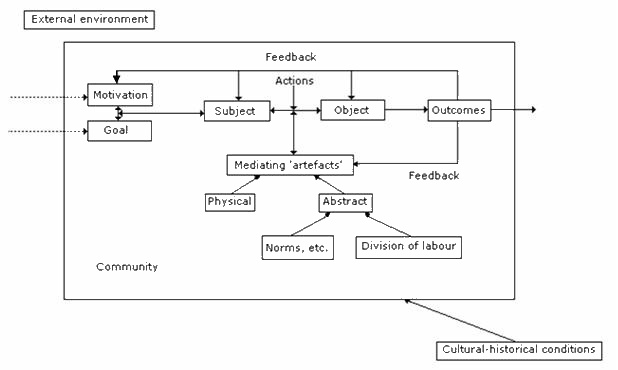

The unit of analysis is the activity system, which is an "object-oriented, collective, and culturally mediated human activity" (Engeström 1999: 9). One could define an activity system as human activity-in-context. Its basic elements are an acting subject, an object that is acted upon, and a tool with which the subject acts upon the object. The subject has a goal with her action, a wished-for outcome. Actions make up activities that are societal: they take place within a community governed by a certain division of labour and certain rules or norms. Usually several subjects act together in a community and not all of them will need to perform all actions. Rules governing the community influence how they work together in any activity: who will do the information seeking, who will make the decisions based on the information, and who will implement them, for instance. The rules and the tools have developed historically and people have learnt to use them. Whether the outcome of an action resembles the original goal depends on how the tools, the societal rules and the actual resources at hand inter-relate.

While Engeström's model has been used in many empirical studies, Wilson (2006) found it too static to do justice to the process character of activities, and it lacked the important notion of goal. He combined Engeström's model with a model by Bedny (2003) and suggested the variation shown in Figure 1.

An activity system is always in development. Different mechanisms cause an activity system to change continuously, but all of them have at their root the internal tensions and contradictions within and between the different aspects and levels of the activity system, as well as between different activity systems. According to Engeström (1987: 82), the fundamental contradiction in any activity system is the clash between individual actions and individual goals, and the total activity system and its motives. Engeström goes on to rank four different kinds of contradictions:

The contradictions and tensions are found on three different levels of operations, actions and activities. The contradictions are not only inevitable, they are also the driving force for change. The tensions lead to changes, which resolve some tensions but lead to new tensions and contradictions, and so on, often moving the activity system from one extreme to the other.

It was decided to study a Swedish youth organization, which is relatively independent from its parent organization, and, which focuses on issues of peace, democracy and sustainable development, with members and activities in different parts of the country. This type of organization focuses on broad and sophisticated goals that should be achieved on a national and/or international scale, but lacks basic resources (mediating artefacts, physical), including competence and basic experience of organizational work (mediating artefacts, abstract). To make sure that young people dominate at all levels, only organizations where at least half of the Board members are under 30 years of age were considered (subjects). Approximately ten organizations in Sweden answer this description.

A youth/peace organization (further, Youth for Peace) with a complex structure of activities and subgroups (division of labour) was chosen: one with many contacts with other national and international organizations and with a geographic spread of members across Sweden (external environment). Youth for Peace is a Swedish youth organization that has existed for around a quarter of a century. At the time of this study it consisted of around four hundred members, of whom between fifty and one hundred were active members (i.e., regularly or sometimes participating in the organization's activities and meetings). In a small group, it was easy to know most of the members socially, which strengthened the feeling of belonging to a community. To become a member, one had to pay a small annual fee.

Youth for Peace catered explicitly to young people. Although they did not have an age limit few active members were over thirty. A typical member is between sixteen and twenty-six, female, Swedish, and a student in social sciences (subjects). This is fairly consistent with the typical membership of peace organizations, which are said to have a relatively small and homogeneous group of members with a high socio-economic background (Vogel et al. 2003: 294-5). However, in the same study most members were said to be middle-aged or older, and the youth of Youth for Peace's members may thus introduce untypical behaviour for peace organizations but answers the requirements of the study.

Only the Board of the organisation and its members were selected for investigation as they mainly deal with information (object) collection and dissemination for all members. Besides, the Board of Youth for Peace has a cycle of activity, which allowed to follow the most important moments from the resignation of one Board through the election, active period and resignation of another (rules).

The choice of Youth for Peace as the study organization provided the opportunity to observe as many aspects of information activities, and as many tensions within and between the activity systems, as possible. From the perspective of this paper, the research question, couched in terms of the theoretical framework of activity theory, for the investigation was:

What tensions and contradictions arise out of the information behaviour of Board members of Youth for Peace?

After a discussion with Board members permission to follow them over a period of a year and a half was received. During this period the Board members in this organization were chosen anew at an annual meeting. In this way, it was possible to follow how Board members handed over their information and knowledge to the new Board and follow this new Board through a whole Board cycle until they themselves could step down. Thus, two Boards were under observation during the period of 2004-2005: the First Board (the final phase and hand-over) and the Second Board (over the whole cycle from election to the hand-over).

| Board | Method |

|---|---|

| First Board | 2 observed board meetings 1 observed annual meeting 8 interviews 26 e-mails 20 documents |

| Second Board | 4 observed board meetings 7 interviews 106 e-mails 319 postings 21 documents |

Three different methods of data collection were chosen: observation of actual Board meetings and of virtual discussions between the Board members; interviews with all Board members; and analysis of organizational documentation. Table 1 shows the application of these methods for each Board.

As noted above, activity theory treats the tensions that can be found within an activity system as not only inevitable, but as the drivers for change in the system. During a year and a half, many smaller and larger disturbances were observed in the information activities of the organization in relation to all the elements of the activity system and between the sub-systems in a bigger information activity system (these are referred to as information activities and specified where necessary). They are analysed in relation to the major tensions that seem to lie behind that set of disturbances.

The tensions described in this part refer to disjointed practices of the Board members and local members that affected information sharing.

In Youth for Peace, the Board members were elected from the local members at an annual meeting. However, as soon as the Board was chosen, a gap opened between the Board and the rest of the members. The non-Board members were suspicious of management and authority as members in a voluntary organization are apt to be (see for instance Handy 1988: 2-9), but they expected the Board to exercise the leadership role that may be more or less vague. The Board members were confused by these conflicting expectations. Several of them thought that their tasks were of an administrative nature and felt distanced from the more direct activities of local members:

... as a board member ... you lose your perspective sometimes on what (Youth for Peace) is working for. You sit so much with administrative issues like finances ... it doesn't feel so tangible that you work for peace when you're on the Board. (Sara).

According to the statutes the Board had to coordinate the activities of local members. However, the flexibility value, one of the major values of Youth for Peace, encouraged all local members to initiate and manage their own projects without regard to the national Board. These projects could be very different as long as they did not contradict the basic ideology of Youth for Peace. The national Board was supposed to 'support' these projects, but lacked tools for distribution of funding or the management of the projects. It made it difficult for the Board members, and for the local members, to understand what this support should be.

One of the main tensions underlying a major disturbance in internal information sharing occurs between division of labour that encourages many different local activities and projects, and the aim to make all members feel included in the same organization.

During the case study, six local projects were conducted in Youth for Peace and totally managed by local members. As all project groups and the Board had different practices and different aims, the Board and the different local projects could be seen as several different communities of practice that had little in common. While information sharing within such communities was rich, it was more difficult to share information between the communities (see Brown and Duguid 1998). The projects happened in different parts of the country, which also aggravated the problem of sharing information. The local groups did not need much contact with the Board to fulfil their own goals. Groups of members and Board members had different interests in the organization, and if the member groups did not share enough common practice with other members, or with the Board, they did not need to communicate or cooperate at a distance, although they might wish more social cohesion or symbolic involvement.

Board members in Youth for Peace were not satisfied by communication with local members, while local members relatively seldom felt the need to communicate with the Board. Board members missed rich contacts with local members and wanted to share as much information as possible with the members, to receive feedback on various issues informally and through formal documentation.

... when I heard from them (local members) it was often a response to something that I had contacted them (about). Usually it wasn't that someone called and just wanted some help, or just wanted to tell something. I missed that. (Barbara)

Mintzberg (1998: 34) pointed out that, if the top manager of an organization in fact consists of a group of people, much and rich communication is essential to be able to make decisions about complex or ambiguous issues (see also Baltes et al. 2002; Daft and Lengel 1984). Similar issues formed a large part of the Board work. The Board members in Youth for Peace struggled to align their wish for feedback and rich communication with busy lives and poor resources.

Rich tools, especially face-to-face meetings, were needed to combat a decline of motivation as the initial excitement wore off and even so, each year some Board members experienced a lack of motivation due to isolation and uncertainty about their actual tasks.

Everyone felt lonely, but no one called the others anyway and tried to get help� (Sonia)

Although there was a clearly expressed need for more contact with other Board members in Youth for Peace, this did not mean that the existing opportunities for communication were always used. The rules and a division of labour aimed at more cooperation and communication, the same Board members who complained about a lack of feedback did not contact the others as much as they could.

Maintaining good 'group dynamics' and developing common practice were seen as important aims by the Board groups. However, disjointed practices within the Board and a lack of clarity about its responsibilities lie behind a set of disturbances. The Board members' uncertainty about the actual contents of Board tasks, and their actual needs for cooperation, led in some cases to an ill thought-through division of labour. Even within the Board, there was little common practice. This, in combination with the distances between Board members prohibiting rich information sharing and the lack of clear-cut tasks, prevented communication, despite understanding its importance.

This part relates to the major differences between the goals and expectations, on one hand, and the outcomes of activities, on the other.

The aims, the plans, and the decisions of some information activities in the organization were ambitious, but in reality much less was accomplished.

The Board members often remarked how difficult it was to reach the priority aim of making Youth for Peace more 'visible' (the activity of sharing information with the environment). Though they discussed the importance of this aim on several separate occasions, they did not seem to achieve much. Board members experienced a lack of competence in media and marketing, but did not try to gain this competence by taking courses or learning from other members as they intended. As a rule, local members and local groups of members also shared less information with the environment than the Boards would have liked.

A similar tendency was evident with the creation of documents. The need for more or updated information products was felt keenly in First and Second Boards, yet many fewer were produced from start to finish than were planned. The information brochure that was much talked about in both Boards could not be finished and was never produced. The documents that were produced often took much longer than planned.

One tension underlying these disturbances seems to be an uncertainty about the division of labour and of power within the organization caused by secondary tensions between the aims, the values and the formal division of labour. Both the Boards and the organization in general were uncertain and insecure about who should create, maintain and implement strategies for communicating with the environment, whose voice should be included in the information products, or who had the authority to enforce the maintenance of a central archive. The tendency was to see all actions as voluntary.

I came up with this initiative and I said, "I will do this!" But I haven't. I feel that is a little annoying ... I will do it ... no one has shown interest. And so I will have to do it by myself. (Bea)

At the same time, most Board members recognized a crying need for a unified strategy:

... it is important to create systems for the information so you know where to get it� So one gets continuity whether it is courses or projects or Board work. (Fabienne)

But the values of the organization contradict centralised action:

... in the local groups, not all write minutes ... or they might write minutes without me knowing about it... (Barbara)

Most members of Youth for Peace were young volunteers whose situations in life were rapidly changing. They had many other interests, such as participation in other organizations, travel, and their own studies and careers, and usually did not stay in one post or in the organization for extended periods. Even active members had varying commitment.

The short time spent by most members on the Board resulted in the failure to complete all planned information products, or to plan and implement complete information strategies. Besides, any member suggesting a task was automatically expected to volunteer for it according to the value of Own responsibility. This could slow the process considerably even when all agreed on the importance of the product or strategy. When the members were not aware of this strong implicit value, no information products or strategies resulted.

The same situation was observed in encountering information from the external environment. Many opportunities for encountering rich information were available in the form of invitations to participate in meetings, networks, joint activities or workshops, there were too few people who had the time or wished to represent the organization. Moreover, many of these meetings took place in the capital, in daytime, which for a distributed organization with few resources meant that even fewer people could possibly participate.

On the other hand, there was too much information pouring in to the office in the form of e-mails, letters, newsletters, brochures etc. The two Boards had slightly different approaches to this overload: the first tried to concentrate on weeding the information, and the second also used the virtual discussion forum and a new e-mail address to spread the information.

A major underlying tension for these disturbances has to do with the expectations from the environment that clashed with the role that the Board had constructed for itself. Organizations and individuals in the environment believed that the chair, or at least the Board, in its leadership and managerial roles, would have the power to make strategic decisions about cooperation or funding, whereas, in most instances, the Board delegated these decisions to local member groups or to the annual meeting. Even when the Board took the responsibility for answering, the chair or other Board members still had to confer with each other, which could take time. Invitations to daytime meetings at the capital also assumed that the Board had the time and the financial resources to participate in them, which it often did not.

The tensions in this part relate to the problems of continuity of organisational work.

When Board members talked about their individual goals for their Board engagement, learning and developing as individuals were often mentioned by the newcomers. Indeed, while working efficiently and setting goals were important aims for the work of the Board according to one interviewee, the actual outcomes did not seem to be as important as the individual development goals of the Board members. Another individual goal many Board members gave for joining the Board or staying on was to influence the organization, although one of them mentioned that the most influential thing she felt she had done in Youth for Peace was to start a project as a local member, since by adding the project to the organization's activities they changed all of its activities.

One of the more important information actions to keep knowledge and information in the organization was the handover between the late Board and the new Board. In this case disturbances were common. In Youth for Peace, the Board members used to share most information about their work and share their ideas at their very last meeting in order to summarize it in some poorer form for the next Board. Strategic documents were traditionally formulated at the end of a Board's term, building heavily on prior versions and giving rise to much common sense-making. But the results could not be acted upon by that Board, and both Boards studied were careful to formulate their plans and strategies so as not to constrain the next Board's freedom, even when this went against the decisions of the annual meeting. Sometimes, when strategies had to be formulated more stringently, the creators added that this 'does not really have to be implemented'. According to Board members, written decisions and policies, which were developed during their own year of office or earlier, did not necessarily have to be followed and could be re-opened for discussion. Thus, the creation of policy documents can be seen as a largely symbolic action.

I feel that we just do this now because we are supposed to do this... (Barbara)

The creators themselves did not have a chance to act upon their own reflections, and the next Board received the information in too poor a context to be able to act upon it.

This will just be one more text that the annual meeting will call 'bad' or 'good' and then the next Board will have to sit and work with it anyway. (Bea)

In Youth for Peace, a focus on the future rather than a desire to know about past activities and plans was visible on several occasions.

You sit such a short time (on the Board) and you have no energy or time to check up on old decisions ... It is a problem, how much voluntary time you should spend on ... checking old things. (Stina)

Flexibility in Youth for Peace had two consequences: (a) the Boards did not want to influence the new Board members by giving them too much information, and (b) new Board members did not often contact late Board members or make use of the information that they received or that was stored in the archives. Maybe this was the reason why it took most Board members several months to understand Youth for Peace, its activities and its environment, and this was commonly accepted, as it was commonly accepted that new Board members had the right to try solutions that might have been tried, and failed, before.

The value of flexibility meant that tasks and division of labour in the Board were changed every year, often before they had settled. The old ones were replaced by new structures and responsibilities by and for a new set of people. The newcomers were in effect asked to set their own tasks without having the experience to consider the implications, and this often lead to isolated responsibilities without contents, frustration and a lack of motivation that was difficult to counteract with the poor resources for communication available.

For newcomers especially, it was difficult to know what one's tasks and responsibilities as a Board member involved. Also respondents reported many different issues they needed information for when first joining the Board. Even more experienced Board members could experience uncertainty about which actions were needed to best support local members and, more importantly, ambiguity about their responsibility according to the division of labour within the Board, or according to the division of labour and decision-making power between Board and members. More or less clear information needs may be acted upon by seeking information if one knows the available sources, but even then it could prove difficult to find the information, as when new Board members failed to contact the previous Board members. In the case of fuzzier information needs, even the information need was unclear, which could cause insecurity and frustration.

There was a tendency to 'let things slide' as a result of a combination of factors. First, new Board members, who were expected to divide tasks and who were responsible for designing and planning for specific areas, were relatively inexperienced in these matters. Secondly, the organizational value of flexibility led new Board members to try to create their own activity anew instead of following clear guidelines. As Lave and Wenger (1991) and Wenger (1998) describe, newcomers to a community can learn faster to become a part of the community's practice if they, while being given access to all information and activities, do not immediately have to shoulder too much responsibility. Youth for Peace allowed newcomers to the Board all access, but also gave them all their responsibility from the start.

This section deals with the issues of formal and informal communication, rules, norms and values.

In many of the information activities in Youth for Peace, an explicit preference for formal channels and formal tools was counteracted by a more informal practice. The 'formality mentioned here does not refer to written rather than spoken tools, as in e.g. Höglund and Persson (1984: 45-47). It refers to the existence of clear and visible rules and impersonal tools and routines. The reasons given for this preference often centred on democratic values and the value of inclusion, but also the aim to maintain continuity in the routines was mentioned. That the importance of formal information increases as an organisation or community grows larger and more mature is confirmed by Wenger (2002). However, in the actual practice of Youth for Peace many routines and tools did not follow their ideal of formality.

Rich tools (Daft and Lengel 1984) are those that provide the possibility of fast feedback when information is shared through multiple cues, including not only language but also visual and other signals. Such tools were preferred in most information activities such as seeking, sharing, encountering and creating documents in Youth for Peace. The preference for rich tools is not surprising: research on managers' information behaviour (Mintzberg 1998; Oppenheim 1997, etc.), on information seeking when dealing with complex tasks (Byström 2005) and on (group) decision making (Baltes et al. 2002) confirms this preference. The power structure within the organization meant that local members should have access to as much rich information as possible to be able to make strategic decisions (see also Nowé et al. 2002). Usage of poorer tools resulted in a lack of feedback or of intellectual access to the encountered information.

When spreading external information among the members, the information often passed three gatekeepers (the staff, the chair, and the rest of the Board) before reaching the local members. Each of the gatekeepers weeded information, so that only a little filtered through to all members. This practice was similar to the way Daft and Lengel (1984) viewed information sharing in hierarchical organizations and not very legitimate in organizations such as Youth for Peace. When sharing information among the Board, richer tools, like the telephone, were preferred in both Boards and rules were made to use it often. But there were some practical disadvantages: it may be difficult to reach others by telephone and it is more expensive. In Youth for Peace, all Board members except the chairs paid their own telephone costs even though their telephone use was budgeted as an organizational cost. Although it is certainly true that there were few financial resources in Youth for Peace to support richer tools, the unwillingness to have the organization pay more than an absolute minimum for the use of rich tools by the Board was also driven by values of fairness and 'not taking advantages'.

Local members on the other hand did not often use the poorer tools that were available for them to communicate because most of their communication was local, which enabled them to share information using rich face to face meetings. That local members clamoured for more interactive (poorer) media to communicate across distance and then did not use them can be attributed to the pervasive value of social cohesion, or inclusion, in the organization. The same tension can be seen in the collective aim of Board members to use rich tools versus their choice of poorer tools in practice.

In contacts between the Board and the local members, it was seen as important to separate the formal contacts of the Board with the members from the informal contacts to ensure that all members would have equal opportunity to contact the board and receive information. In practice, the division of labour built mostly on such informal contacts, which was more efficient, especially since the division of labour was fuzzy and the different contacts with members overlapped.

Overall, the lack of financial resources was a basic tension underlying all activities and decisions in the boards, which was strengthened by the value of not taking advantage and by the inexperience of the board members in budget matters. It constrained which information activities could be engaged in, to which degrees, and using which tools.

Thus, aims and goals to save time in information actions as well as the value of flexibility worked against the aim to create more formal tools and routines in the information activities to ensure continuity, inclusion and democracy.

This research has demonstrated the usefulness of the activity theory approach to the analysis of information behaviour in context. In particular, the notion of tensions and contradictions has enabled us to identify and extract from the volume of interview transcripts those aspects of the context and content of Board work that influence information behaviour.

From this analysis we see that a number of contextual factors affect the information behaviour of the Board members studied. First, the values of the organization as one in which democratic values prevail, where flexibility is valued, where taking advantage of one's position is disapproved of give rise to contradictions in relation to the management of information activities and in the behaviour of Board members that detract from the effectiveness of the Board and the organization.

We also see that there is an inherent contradiction between the voluntary nature of the contributions of members and Board members in particular. Their time and other available resources are limited by the voluntary nature of work, but it is necessary if the ideals of information sharing and democratic decision making are to be achieved.

The informality of interaction and the rejection of bureaucratic norms in communication, information exchange and the management of information processes also has implications for the formal functioning of the Board and, hence, the organization. The extent to which one Board builds upon the experience and activities of previous Boards is minimal, partly because of the failure to transmit learning effectively and partly because of the value attributed to members of the Board learning on the job and doing their own thing.

However, the values of 'doing their own thing', 'flexibility' and 'equality' helped to achieve one of the main goals of a voluntary youth organization: practical acquisition of basic information skills related to participation in a democratic body. The efficiency of information seeking and production was sacrificed, but every member of the Board had a possibility to learn a variety of jobs by hands-on practice: create a job description, write minutes of the meeting, work on information brochures, etc. Thus, despite seemingly inefficient information practices, the voluntary organization achieves its main (though unofficial) goal.

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referees for valuable comments that helped to improve the paper and the members of Youth for Peace who were the most important collaborators in this project.

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

© the authors, 2008. Last updated: 12 December, 2008 |