vol. 15 no. 4, December, 2010

vol. 15 no. 4, December, 2010 | ||||

Long-term digital preservation is one of the highest priorities of many agencies supporting and funding research. One simply has to look at the abundance of projects on the topic conducted over the last ten years: to name just a few, PRESTO - Digital preservation technology (Wright 2001), Digital Preservation Europe (Digital… 2006); LIWA - Living Web Archives ( Living… 2008); PLANETS - Preservation and Long-term Access through Networked Services (PLANETS 2007); CASPAR - Cultural, Artistic and Scientific knowledge for Preservation, Access and Retrieval (CASPAR 2006); SHERPA - Digital Preservation: Creating a Persistent Preservation Environment for Institutional Repositories (SHERPA 2006); Digital Preservation Lifecycle Management: Building A Demonstration Prototype for the Preservation of Large Scale Multimedia Collections (Rajasekar n.d.). The agencies include the US Government, the European Union, the UK's Joint Information Systems Committee, and similar organization in other countries. Some of the projects concentrate on more general digital preservation theory and its technological implementation, others focus on certain domain areas, such as culture, art, heritage, research and education, industry, engineering, or publishing. or on certain types of institutions: memory institutions (archives, libraries and museums), producers of databases, large scientific organizations (like NASA), private companies or public departments facing the need to preserve data and documents.

The aim of this paper is to demonstrate the role that information behaviour research may play in information system design. As a result, our work is closer to the information requirements literature of information systems research than it is to information behaviour research. We would argue, however, that it is important for these fields to come together, particularly in the world of digital information resources. From the methodological point of view we explore the value of use cases in defining information requirements and consider their wider application in information behaviour research.

The paper draws upon two streams of data analysis: first, an analysis of the literature on long-term digital preservation systems (and, to a degree, digital libraries) and secondly, analysis of interviews undertaken in the course of the SHAMAN project.

The preservation of the cultural, organizational and even personal record has been, until the very recent past, concerned with books, unbound paper documents, film negatives, slides and prints, movie films, radiographic images, and a thousand and one other 'documentary' forms. The physical space requirements for the long-term preservation of these materials are enormous: for example, at the end of 2009, the British Library opened a new storage facility in Yorkshire with 262 kilometres of 'shelf space' (Pembrey 2009) and, in part, digital preservation of records of these kinds is seen as at least part of the solution to the increased demand for physical storage. We leave out of consideration here the need to preserve actual objects of culture, such as painting, sculptures, tools and archaeological artefacts, necessity to digitise images of these objects and also to take such accurate measurements that it is possible to reproduce physical objects such as sculptures (Digital… 2010). These data may be digitally preserved so that, if the object is lost, an exact copy can be automatically reproduced, potentially in the same material as the original.

In addition to the digitization of existing physical materials, there is the increasingly significant body of born-digital material, which covers not only such things as e-mail, word-processed documents and spreadsheets, but e-books, sound recordings, films, scientific data sets, social science data archives, health-related patient data and many more. To these we can add the entirety of the World Wide Web and, possibly, millions of organizational intranets. It has been claimed that there is now so much born digital material that it will be impossible to store it all: thus, in 2007 the amount of data produced more or less equalled the available storage capacity but production and storage capacity are diverging so rapidly that it was estimated that by 2011 'almost half of the digital universe will have no home' (IDC 2008: 2).

In this context, long-term digital preservation has particular problems: first, there is a proliferation of file formats for almost every kind of 'document', only some of which will survive into the future. Consequently, ways must be found to ensure that obsolete formats can be interpreted in the future. Secondly, the technology for producing, storing and reading digital files is changing constantly. The most obvious example is in portable storage: we have gone from 8 inch floppy discs, via 5¼ inch, to 3½ inch and on to zip drives and discs, CD-ROM, DVDs and, now, USB drives. Does anyone own an 8 inch floppy drive, or even a 5¼ inch drive? Such things are no longer installed in computers. The result is that files prepared for obsolete technology, may also be unreadable in the future. The best known example of this is the case of the BBC's Domesday Project (Finney 2009), which recorded information about British society in the 1980s, celebrating the original Domesday Book, which was compiled after the Norman invasion of Britain in 1066. The technology used for the project was the interactive videodisc, which rapidly proved not to be the technology of the future. A further project (CAMiLEON) was launched to retrieve the information from the videodiscs and a successful emulator was developed (Darlington et al. 2003) To date, however, no means has been found to make the project material generally available and, as it cannot be used, it is to all intents and purposes, still lost.

One of the projects funded by the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme, SHAMAN - Sustaining Heritage through Multivalent ArchiviNg, builds on many earlier technological developments and directs its efforts, "to supply a comprehensive, systematic and dynamic means for preserving any type of electronic record, free from dependence on any specific hardware and software" by integrating data grid, digital libraries and persistent archive technologies (Watry 2007: 41).

The development concentrates on building the prototypes for the institutions in three application domains: heritage preservation in memory institutions; industrial design and engineering data preservation in companies; preservation of scientific data collections in e-science area. A key element in the Project is the adoption of data grid technology to facilitate intercommunication among participating archives. To be accepted by the target communities the solutions provided by the research and development activities have to answer the existing needs and moreover to take into account the existing practice and legacy systems. The user communities targeted by the project are rather different from the point of view of the preservation activities carried out in them, the experience and understanding of preservation problems, and also by the previous investigations into their long-term preservation needs.

The fundamental aim of the SHAMAN Project is to overcome the problems set out above in the development of a framework for long-term digital preservation. The specific aim of SHAMAN is encapsulated in this statement from the Description of work:

Effectively, we need to send into the future not only the information, but also a description of the environment that is being used to manage and read that information. Thus, the proposal differs from the current generation of digital preservation projects, which are primarily focused on the short-term management of preservation services and not solving the fundamental problem of technological obsolescence. (SHAMAN 2007: 5)

To accomplish this, the Project has identified four principles upon which the systems must be based:

- Authenticity, assertions about the provenance of the records.

- Integrity, assertions about the management of the records.

- Chain of custody, assertions about the ownership of the records, and

- Context of production, preservation, access and reuse. (SHAMAN 2007: 5)

and is in the process of developing tools for "analysing, ingesting, managing, accessing and reusing information objects and data" (SHAMAN 2007: 3). As part of the process, investigations have been carried out into the user, operator and organizational requirements for systems development, the results of which are reported here.

The kind of long-term digital preservation system proposed by SHAMAN is novel and, consequently, the literature available on the different kinds of requirements is rather limited. What we have attempted, therefore, is an analysis of the literature on digital libraries and digital preservation more generally, with the aim of arriving at a conceptual framework for research and proposals for further investigations.

From the literature, we can identify four broad categories: society at large, generating requirements for long-term preservation, which are often only implicit in papers on the general need to preserve a culture; organizational requirements, which will vary depending upon the nature of the organization, for example, whether it is a public sector organization like a local authority or a business firm; organizational staff who must operate the preservation system, undertaking the functions of ingest, access and delivery to end-users; and, finally, end-users in the normal definition of the term, i.e., members of the organization who need to draw upon the digital resource, or scholars, students and members of the general public who may need access to help them with their work, study or research.

We begin our analysis at the societal level, partly because it is in this area that the literature is so scarce, but also because the requirements set by society affect the requirements of the other actors. Generally, society's needs are usually spoken of in terms of the need to preserve the record of the society's culture over time; for example Drijfout (2001) notes that a failure to ensure long-term preservation, 'will damage future scholarship and weaken our scientific and cultural heritage'. Smith (2007) provides a more detailed analysis of the notion of the social value of preservation.

We can examine organizational needs from two perspectives: first, the requirements organizations have for long-term preservation systems; that is, what must such a system do in order to be useful to the organization? Secondly, we can consider what information an organization needs in order to make decisions about the choice of systems and in making policy decisions about long-term preservation in general. The literature on the first of these perspectives is much more extensive than on the second; in fact, our searches have produced no research papers that deal with the second issue. We can, however, make some reasonable guesses about what is needed.

The organizations with which we are chiefly concerned in the SHAMAN Project are those concerned with the preservation of the cultural record. Clearly, there is considerable overlap, in such cases, between the needs of the organization and the needs of society. 'Cultural memory' institutions are, in effect, the agencies tasked by society to deliver preservation of the cultural record.

A major project exploring the issue of choosing a preservation strategy has been the DELOS Project. This Project evolved a process for choosing a preservation strategy, using utility analysis (Rauch 2004), and proposed that organizational needs could be categorized under four headings: file characteristics, record characteristics, process characteristics, and costs (Strodle et al. 2006). To these, we would add a fifth, which often appears in such lists, the knowledge required by staff who operate or use the system. The four categories presented by Strodle, et al. are what they call 'top level' categories, which include much more specific elements: thus, in the case of file characteristics, the category includes appearance, content and structure and, at an even lower level, such matters as image resolution, macro support and embedded metadata. The significance of file type ought not to be underestimated: a study carried out at Göttingen University (Neuroth et al. 2006) revealed a total of ninety-six different file formats used by the staff of the university and, additionally, some proprietary formats were in use with specific software.

We have in mind here, the needs of those members of staff of the organization who manage and operate the long-term preservation system. We can group such staff into three categories, which we shall call, technical, management and service staff. Technical staff are responsible for the maintenance of the systems and any digitization that may be done, management staff are responsible for selecting and, in some cases, acquiring materials, allocation of metadata, ingesting (a term used by the preservation community to denote uploading) materials and other document management issues, and service staff are responsible for delivering service to users from the digital resource.

In other words, there are a number of different roles associated with digital preservation and, in its requirements study, the SHAMAN project has identified roles such as, preservation manager, collection manager, technology manager and auditor.

The literature on what organizational staff need of a system appears to be almost non-existent. The focus appears to be on the new skills that staff may need to function in the long-term digital preservation domain. For example, in the allied area of Web archiving Murray and Hsieh (2008) found that librarians were concerned about issues such as how to select material for digitization, how to assess the authenticity of materials, how to cope with the increased load of metadata production and cataloguing, and how best to provide access. We have been unable to locate an equivalent study for long-term preservation systems, but it seems likely that the same issues will arise.

Again, the very idea of long-term digital preservation systems is so new that the needs of the ultimate user, the scholar or citizen who needs access to the digital record, have not been explored. The closest we come to the digital archive user is the digital library user and we can imagine that the two will have at least closely associated needs. Even here, however, the literature on user needs is limited: much of the material found deals with issues such as search behaviour, or the design of personal access portals, or aspects of information retrieval, and other problems. In fact, we found only three papers that offered ideas that fit our conception of the notion of end-users' needs.

First, Xie (2008) sets out the criteria according to which users assess digital libraries (in this case the Library of Congress's American Memory site), listing interface usability, collection quality, service quality, system performance and user satisfaction. Within these categories one can find a number of finer-grained variables: for example, under collection quality we have scope, authority, accuracy, completeness, currency and copyright, all of which would apply to a long-term preservation system, but, in the case of the SHAMAN Project we would add, because of the need to migrate digital resources between different technologies, integrity, that is, the user will expect the original content of the document to be preserved as it was at the point of ingest to the original system.

Secondly, Inskip et al. (2008), after exploring the needs of users of a folk music collection, note that if the search process of a user is reflected in system design for a digital library then it would include the provision of background information to an item (and this may be as true for a memory institution's archive item as for a folk song), browsing capability, links between sources (again, true of much digital archive material) and links to other information sources.

Finally, Abdullah and Zainab (2007) point to more directly systems-oriented issues: registering and managing user information; creating reports and uploading digital objects (how far the latter would be allowed would be a matter for preservation policy); searching for and retrieving information; indexing digital resources (a long-term preservation system under the SHAMAN model would have metadata performing this role, but we can imagine a personal access system, perhaps based on the user's own server, which allowed tagging by the user); system network robustness (where the SHAMAN proposal for the use of grid technology would help); and the system operation schedule and the extent to which it managed and controlled access.

A composite set of these requirements together with those already developed for the SHAMAN Assessment Framework, constitutes, in our view, a valid framework for the analysis of users' needs.

The SHAMAN project may serve as an exemplary node of all the problems outlined above. It focuses on the development of the preservation technology, which, though building on earlier research and developments, has to meet the future requirements of long-term preservation of many interested parties. The problems faced by long-term preservation in the digital environment are quite well known and many of them have been decomposed into a variety of aspects and elements while looking for solutions as one sees from the literature analysis. Despite this, there are quite significant obscure areas, especially with regard to the future infrastructures, actors, policies and digital resources themselves.

Therefore, investigating these future requirements for the technologies that do not yet exist is a significant issue, even if system developers are used to defining system requirements. The difficulty, in this case, was recognized by the project partners at the very beginning and they began by collecting data about existing needs for long-term digital preservation and about the exploitation of existing systems of this type in working environments. We also used significant work done earlier in establishing the requirements for trusted repositories (TRAC) (RLG-NARA… 2007) and defining risks for long-term preservation of digital information (DRAMBORA 2008). In addition, a certain leap of imagination was allowed to fill in the gap between the known practices or expressed needs and the unknown future demands.

The nature of the SHAMAN framework itself also posed a number of difficulties - one of them was the need to take into account the requirements posed by system's end-users, i.e., librarians, curators, archivists, and also end-users of the preserved documents, for example, scholars, students and members of the public. There was also a group of the system users, less visible than the other two groups, that is, publishers, owners of intellectual property and producers of digital objects, who were submitting them for preservation. This group introduces problems of its own: it is interested in preservation of their products and in developing access services and, though not doing this itself, nevertheless wants to safeguard its interests and creates other requirements important to both processes (preservation and access).

Besides, the SHAMAN framework is intended to become a universal solution for long-term digital preservation. Therefore, the project addresses three quite different domains of focus that have become main sources of data collected for the development of system requirements.

The three domains of focus for the SHAMAN project are: memory institutions, which have been interested in the preservation of our documented heritage for a long time and have developed different approaches to restoration, conservation, and preservation of various collections of many different objects (written, visual, audio, natural and cultural objects); engineering and industrial design organizations, which have very different attitude towards digital preservation. They are commercial organizations and digital preservation has legal (e.g., contractual) and economic implications. For example, the re-use of designs may help saving development time and so reduce development costs. So far, however, little has been done in this area (Heutelbeck et al. 2009); and e-science groups and institutions, where we see increasing use of digital technologies in research work for processing huge amounts of digital data in natural and technical sciences generated by modern data collection technologies and where the actual digital preservation needs of researchers are actively supported by funding agencies and explored on different levels and in different contexts (see, for example, Lord and Macdonald 2003).

The differences between the domains are quite significant and this adds to the challenge of investigating the needs for long-term digital preservation.

The bulk of data collection for establishing the requirements for long-term preservation technology was done during the first year of the project (2008). However, it is regarded as an ongoing process affecting each stage of prototype development. Thus, the evaluation of the emerging technological solutions by the customer organizations and end users is regarded as further user requirements' data fed back into the process of research and development to guide the process.

When exploring complex problems in which the unknown, or uncertainty, or both, prevails, the research methods usually recommended are those which help researchers to understand the nature and the key elements of the problem better, i.e. approaches that allow the structure of the explored phenomenon to emerge from empirical data (Layder 1998: 26-27). Usually, this approach requires the use of qualitative methods of data collection and interpretation. However, the underlying epistemology does not have to be exclusively interpretative. Within a technology-oriented project such as SHAMAN, which is inevitably based on positivist epistemology, it is important that underlying methodological assumptions in different parts of the project do not contradict each other. (SHAMAN 2009: 5)

Contextual enquiry is one of the most suitable modes of positivist enquiry using qualitative methods for establishing how a particular process is performed by actors and what actual needs and requirements they and their tasks impose on the variety of tools and systems used in the process:

Contextual inquiry is an explicit step for understanding who the customers really are and how they work on a day-to-day basis. The design team conducts one-on-one field interviews with customers in their workplace to discover what matters in the work. A contextual interviewer observes users as they work and inquires into the users' actions as they unfold to understand their motivations and strategy. The interviewer and user, through discussion, develop a shared interpretation of the work. (Holtzblatt, 2001: 19)

The whole process of data collection and analysis for the project was also guided by the concept of the Open Archival Information System (OAIS), set out in 'Recommendations for an OAIS reference model' (CCSDS 2002).

The data used in this paper were collected during a qualitative stage involving semi-structured interviews with the actors in the organizations working in the three SHAMAN domains referred to above. Whenever possible, a semi-structured observation session was applied and additional documentation was collected on site. Three different interview schedules were developed for policy makers and managers, for end-users of the preservation system (such as data curators, IT staff) and consumers (users of preserved information). Twenty interviews were conducted in eleven organizations. A slightly different approach was taken in the domain of industrial design and engineering as there were no actors such as preservation managers or data curators and archivists because of the absence of preservation activities. Data were collected through prolonged observation and exploration of the practices in partner organizations and discussions with relevant persons.

The collected data was processed using the highly formalized Universal Modelling Language to extract abstract information about standard users, use cases and user scenarios. Both sets, i.e., the interview transcripts and the extracted information are used in the following part of the paper.

The interviews provided deep insight into the existing practices of archiving, storing and preserving different digital materials (texts, images, visual and audio recordings, data files of different formats) in a limited number of institutions in several countries. Some storage of digital objects was found to be present in all selected organizations. However, they were very different in maintaining and re-using the stored material.

Memory institutions with a mandate for a long-term preservation and some scientific groups with deep interest in the re-use of research data have elaborate policies and practices directed towards long-term digital preservation, which include:

Some scientific organizations and industrial design companies still do not make a clear difference between the archiving function and preservation and are not concerned about future re-use of their digital resources. Usually this may be associated with the policies of the parent organization and/or traditional practice.

The organizations with developed preservation policies usually also follow technical standards, procedures and rules in all work stages. They have good grasp of the arising technological problems and either have found, or are looking for, solutions. They usually plan to expand their preservation activities, some of which may be limited by existing resources or the lack of appropriate technologies to achieve the goal.

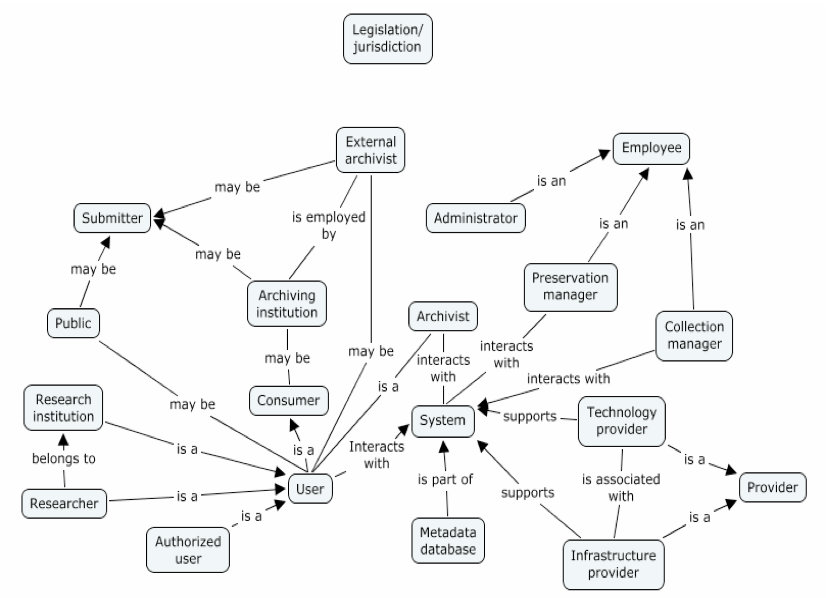

On the basis of the interviews with the representatives of the e-science and humanities groups a conceptual map was drawn to represent a generalised picture of relations of different actors in preservation:

The actors (users, providers, employees or submitters) on the contextual map include not only human beings but also other entities, such as a system or legislation or an organization. All of them may interact with the system to access digital objects or metadata about them directly or through a mediator (Archivist).

The first step of this analysis led to the development of a number of primary system requirements and use scenarios.

The analysis of the data has produced eleven primary requirements for the system. Some of them, like automatic meta-data extraction or enhanced functions of document discovery, may also be found in other information systems. Others, such as scalable storage capacity or security and trust requirements, would be expected in relation to preservation. Memory institutions that are already working with archival systems need technology that is compatible with these systems and which allows access and use of the data preserved in them. We will have a closer look at several less predictable requirements.

The interviews show that there is a need for viewing data in obsolete formats without migrating it to a new format. This was expressed mainly in the form of complaints about cumbersome migration processes.

This requirement naturally includes the necessity to preserve and manage the provenance of digital data, which enables re-tracing of the preservation process. But it is not enough to capture the context of the document. The preservation system needs to capture the context of digital objects in production and working environments and their history. At present, much of this information is not embedded in the document itself, which creates a problem that may be addressed by developing policies and rules rather than technologies. Capturing the information about the preservation system and technology used at the time of the document creation or ingest would enable the maintenance of the document's authenticity and integrity in the future.

On the basis of the interviews a number of use cases were developed for each domain of focus: forty-one for memory institutions, thirty-nine for industrial design and engineering, and thirty-six for e-science.

A use case relates to some functionality performed by a system. Each use case constitutes a complete course of action initiated by an actor, and specifies the interaction that takes place between an actor and the system, indicates the goal of the action and identifies other actors involved. 'Actors' may be persons or 'abstract' actors such as other systems and/or sub-systems of the system under observation (Bittner and Spence 2003). The Universal Modelling Language has become the de facto standard for developing use cases.

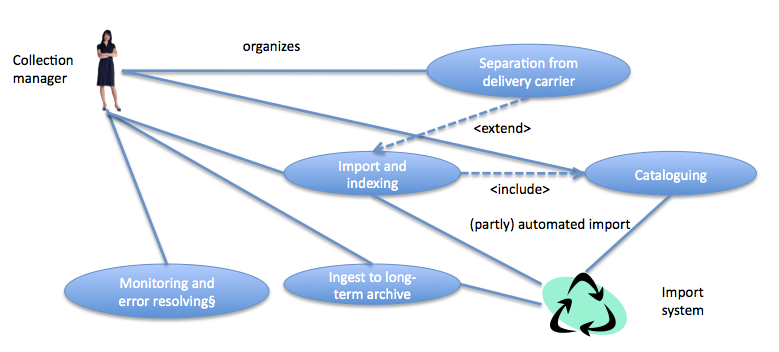

Figure 2 below demonstrates the nature of the use case. In this example, two actors are seen: a human actor, the Collection Manager, and an abstract actor, the Import System. Five use cases are observed in the diagram (the blue shapes), with the lines and relationship statements indicating the connections between the cases and the actors. The diagram shows that the Collection Manager is responsible for organizing the separation of the data relating to a digital object from the delivery carrier (i.e., the bit stream that carries the data), as well as for managing the manual import, indexing and cataloguing, before the metadata and the digital object are imported (partly automatically) into the Import System (a sub-system of the preservation system). The term <extend> simply means that the actions of use case Separation from the delivery carrier are continued in use case Import and indexing. The term <include>' means that use case Cataloguing is included in use case Import and indexing, but can be separately distinguished from other operations there.

The individual use cases are described in a standard format, as shown in Table 1 for the use case of cataloguing:

| ID | UC-DOF1-323 |

|---|---|

| Name | Cataloguing |

| Actors | Collection manager |

| Brief description | The new object is incorporated into the institutional catalogue.

Included by UC-DOF1-320 (Import) |

| Preconditions | Initiated by the import routines (UC-DOF1-320). |

| Action | Descriptive metadata fulfilling the catalogue schema of the memory institution is generated. Generate catalogue/knowledge base entry. |

| Post-conditions | Object is incorporated in the catalogue |

| References | See UC-DOF1-320 |

The use cases define both stereotypical actors (such as Collection Manager) and stereotypical activities (Cataloguing). From the point of view of system design, this is essential because of the need for general descriptions of behaviour. There will be individual exceptions in the way Jack or Jane or Sally function as Collection Managers, but systems have to be designed to cope with the generality of behaviour, not with the myriad exceptions.

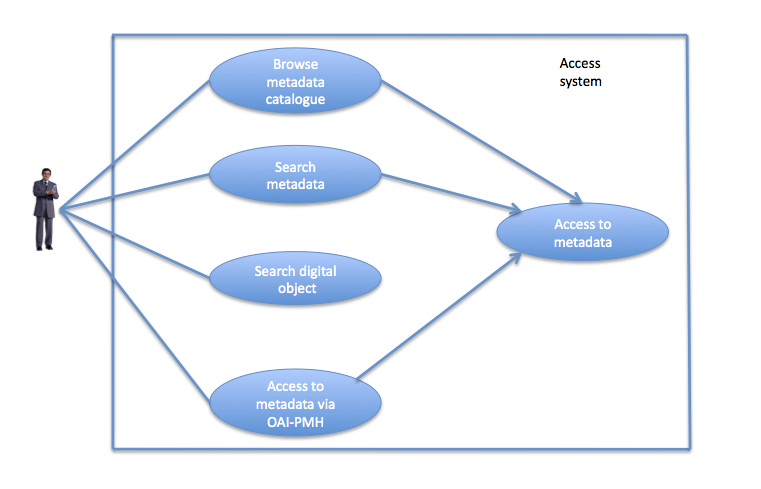

Figure 3 shows another set of use cases associated with the Consumer (or end-user, as it would be termed in information behaviour research). Here, three of the use cases are associated with another use case, and all function within an abstract actor, the Access System. Again, we illustrate the content of a use case (Browse metadata catalogue) with Table 2.

| ID | UC-DOF3-520 |

|---|---|

| Name | Browse metadata catalogue |

| Actors | Consumer |

| Brief description | The metadata are made accessible through a catalogue that allows the user to browse according to some defined criteria such as collections or domains |

| Preconditions | The user has the right to access the requested metadata |

| Action | The user browses the metadata catalogue in order to find metadata entries which describe digital objects he is interested in. |

| Post-conditions | |

| References | DOF3B-15, DOF3C-E3 |

Note that in Table 2, there are no 'post-conditions', that is, nothing happens in the system as a result of the Consumer browsing the catalogue.

These two brief examples illustrate how the original interview data have been transformed by the Universal Modelling Language processes into descriptions of use cases involving both human and system actors.

One of the continuing debates within (and outside) the information behaviour research community is the relevance of such research for the development and design of information systems. In the case of the SHAMAN requirements definition process, we have seen collaboration between information behaviour researchers and information systems researchers in which the qualitative data from interviews has been employed to identify 'stereotypical' users and use cases. We suggest that this collaboration has been very fruitful, with the system designers being given much richer data on the behaviour of system actors than is normally the case.

The gap between information behaviour research and information systems design has been exacerbated by a focus, within the former, upon the behaviour of individuals. The concern has been to show how individuals differ in their behaviour and to elicit the reasons for these differences. Long-term preservation systems design and development, however, requires an understanding of the generality of actions performed in the preparation of the digital resource, its manipulation within the system and its use by system managers, operators and end-users.

We suggest that the apparent failure of information behaviour research to influence information systems design (including information retrieval systems) is not the result of some inherent flaw in research methodologies, but lies in the lack of interaction between information system designers and information behaviour researchers. Generally, information behaviour researchers will not be part of a system development team, rather, they will be pursuing some research topic independently. The value of the work reported here is that it demonstrates that information behaviour research can play a role in systems design and that, far from having their perspective rejected, information behaviour researchers are welcomed as full partners in the process with a great deal to offer in terms of methods and perspectives.

Virtually every civilization has assumed that the arrangements made for the preservation of its culture would survive into the indefinite future. At best, long-term preservation has been only partly achieved. For example, the rich culture of ancient Greece survives only partially; there are more lost dramatic works, for example, than those that survive. Similarly, the eruption of Vesuvius destroyed a number of libraries and, although modern technology may be able to revive some burnt papyrus rolls, it is unlikely that all will be recovered. The loss of the great library of Alexandria is well known, but less well known is the loss of the great library at Wearmouth, in the North of England (where the Venerable Bede wrote the first history of the British people) as a result of the Viking invasion of Britain. War and natural disasters have been the enemies of long-term preservation and, at this point in history, we do not know whether the arrangements now being made will enable preservation of the cultural record for another thousand years, or five hundred, or even a century.

Nevertheless, the effort has to be made and, as we have shown, there are many projects in progress and completed that have long-term preservation of digital resources as their focus. The aim of SHAMAN is ambitious: it is to develop a framework to enable the design and development of systems that will ensure that what is produced today, in digital form, can be re-used at any time in the future, whether or not the software and the hardware that enabled the digital production continue to exist or not. Thinking about the future needs of the operators, managers and users of such systems is an optimistic endeavour, since we cannot know the nature of future systems or the needs and behaviour of future users. However, the firmer the base upon which preservation systems can be built, the more likely it is that future archivists and users will be able to explore the digital record of today.

Our ability to develop such systems, however, depends crucially upon our understanding of human behaviour in relation to systems and upon being able to identify not only differences (that may explain system failures, for example) but also similarities and stereotypes. The Universal Modelling Language with stereotypical actors and use cases offers information behaviour researchers a way to engage with system developers in a creative synergy.

Elena Maceviciute is Professor in the Swedish School of Library and Information Science, and in the Faculty of Communication, Vilnius University, Lithuania. She obtained her PhD at Vilnius and Moscow universities and is currently working on the SHAMAN project and in the area of scholarly communication and communication theory. She can be contacted at [email protected]

Professor Tom Wilson is a Visiting Professor at the Universities of Boras (Sweden), Porto (Portugal) and Leeds (UK), and Professor Emeritus, University of Sheffield, UK. He received his BSc in Economics and Sociology from the University of London and his PhD from the University of Sheffield. His research has spanned a number of areas, including information management and information behaviour. He can be contacted at [email protected]

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

© the authors, 2010. Last updated: 10 December, 2010 |